Dawn Chanland, Steven Cox, Jim Foster

Date Accepted: April 14, 2016 PDT

Keywords: diversification, marketing management, hospitality, management

CASE SYNOPSIS

Jim Foster and his father started an Irish pub, The Selwyn Pub, in an upscale Charlotte, North Carolina neighborhood in 1990. Originally envisioned as a casual dining restaurant with an Irish pub like atmosphere, Jim and his father soon discovered that their customers were looking for a place to drink beer and eat pub food. Recently, they noticed a shift in the customer demographics and drinking preferences at the Pub. Seeing a significant growth in the number of women that frequented the pub and the number of times they requested wine led Jim to expand the wine offerings in their pub. The problem is that neither had much experience with wine, and they had a young and rather inexperienced wait staff who are not familiar with wine either. The case examines a fundamental question for any business; that is, whether to grow into new, unfamiliar product categories to meet changes in customer preferences or stick with the existing core competencies?

It had been an interesting experiment. In March 2014, in response to the growing demand for wine in his successful Irish pub, The Selwyn Pub, in Charlotte, North Carolina, Jim Foster decided to expand the wine offerings at the Pub. Much to his surprise, wine sales grew rapidly. Unfortunately, while Jim understood the beer business, he knew that he was out of his element when it came to wines. The plethora of wine varieties, vineyards, growing regions, and price points seemed endless. On top of that, his wait staff was composed mostly of college students and turnover was frequent. After steep growth in wine sales for the next six months, by September 2014, wine revenues had leveled off. Jim wondered if this was because of his choice in the variety of wines he had been selecting, or the ability of his wait staff to promote the wine. He felt that he needed to make a decision soon, fall was approaching, and it was traditionally one of his most profitable seasons, but what decision? He could consider his wine expansion an interesting experiment and return to the Pub’s beer roots, be content with the growth in wine sales and continue without any additional changes, or move more aggressively into wine offerings and make the changes necessary to grow his wine sales. Jim felt that it was time to decide.

BACKGROUND

Jim Foster and his father had a history of partnering together in their careers, ultimately leading to opening a pub together. For many of Jim’s formative years, his father had been a teacher and basketball coach who managed bars and bartended during school breaks to earn additional family income. When Jim was 18, his father taught him how to bartend. After Jim’s father “retired” and relocated to North Carolina, he was offered a junior college basketball coaching position; his father’s first official decision on the job was to hire Jim as his assistant. They had a rewarding and exciting time for some years as head and assistant coach.

Having learned that they could successfully work together, they began to consider other endeavors they could embark upon as a team. Although Jim was leveraging his law degree and his certified public accounting licensure to lead a successful tax attorney practice, he determined that investing in a restaurant with his father was a viable option. Jim had fond memories of his years at Albany Law School in upstate New York during when he worked in an Irish pub. He loved the ambiance of the pub, a comfortable place where everyone in the neighborhood could relax with good friends.

When in the early 1990s, a small Cuban restaurant in the affluent Myers Park area of Charlotte became available, Jim and his father decided to follow their dream and take a long-term lease on the property. As Jim had hoped, his Pub’s clientele was younger, affluent residents of the neighborhood. The patrons were about 60 percent male. The Pub also catered to the same demographic of white-collar workers who did not live in Myers Park but found the Pub convenient when returning home from work. The property had several advantages: first, its location was in the heart of Myers Park, an area that was considered a very fashionable place for 25 to 45-year-old professionals to live; second, the location was on the main thoroughfare enabling easy access; and third, the location had room to build an outside seating area capable of serving 100 customers. On the negative side, parking was limited during weekday working hours; however, in the evenings and on weekends, patrons could use the adjacent parking lot reserved for several small businesses on weekdays. Also, inside seating was limited to a capacity of 45 patrons. Finally, the kitchen was small, and, due to zoning regulations, expansion was not possible.

They took a risk in what they saw as an opportunity; they built a patio out front near a large oak tree on the property to increase seating capacity and offer people an option to commune there. The decision was a boon for them; outdoor patios had not been fashionable or common in Charlotte until that time, but it turned out that customers showed up in droves to sit outside. Business boomed. The Pub was voted the best pub in Charlotte by the Charlotte Magazine in 2010 and 2012, and the best Neighborhood Pub in 2013 and 2015.

Although Jim’s education and experience had been in law and accounting, and his practice was thriving, Jim was unfulfilled with his then full-time career. He had joined the Queens University of Charlotte faculty and found himself spending more time with the Pub, which was increasingly gaining a loyal customer base. Ultimately, he became more active in managing the Pub and sold off his ownership of his practice. Further, as time passed, Jim’s father was less and less involved in the management of the Pub.

Their decision to open a pub turned out to be a good one. Focusing on a friendly atmosphere where young professionals could drop in, the Pub quickly became a favorite spot. The Pub had received high marks from Trip Advisor reviewers and was even mentioned in Kathy Reich’s book Death Du Jour. The Pub focused mainly on beer rather than liquor or wine sales (the Pub offered only one white and one red wine, a Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay, respectively) and had an assortment of 25 different brands on tap or in the bottle. To avoid attracting a rowdy or non-professional crowd, they maintained a strict policy of not offering cheap beer specials.

There were no happy hours, no dollar beer specials, and no two-for-one deals. As Jim considered the mix of regular customers, he felt that the policy had worked well.

From the beginning, the Pub offered a relatively standard mix of “pub” food. The menu consisted of salads, fried foods, wings, and pizza. Jim had taken several cooking classes at the Culinary Institute of America and collaborated with his food vendors on a regular basis to ensure that his menu was in keeping with the Charlotte food scene. Jim believed in using only the best ingredients in his recipes. Hamburgers were 10 ounces of the highest quality beef; chicken wings were large and, after cooking, sent through the pizza oven to enhance the flavor; and pizzas were hand tossed and only fresh toppings were used. Also, fried pickles came to be a local trademark for the Pub. As a result of these improvements, Jim commented that he “thought that customers would begin to think of the Pub as a place for a bite and a drink rather than a drink and a bite.”

To increase the popularity of the outdoor space and to expand the seating capacity of the Pub, in 2010, Jim made a significant investment in a patio upgrade. He put in fireplaces, upgraded the seating, and added a large aluminum awning. With the later addition of outdoor heating, the patio soon became more popular than the inside of the Pub. An unexpected consequence of the change, the customer demographic changed slightly, and he began attracting more female customers, especially an after-work crowd. While the Pub had always been an attractive location for the male after-work banking set, now it was attracting more and more women.

Changes in Drinking Preferences

Jim had noticed two significant changes in the alcohol consumption choices of his customers. First, while beer sales continued to grow, his customer preferences were tending toward the higher-end craft beers. In fact, in the past three years, craft beers sales had tripled and represented 20 percent of his beer sales. Responding to this change, Jim had doubled the number of craft beers on tap.

The growth of craft beer sales was a welcome change for the Pub. The per-glass and bottle prices were often 50 percent higher than regular domestic beers, and the margins were equally higher. Jim attributed this change to three factors: the increasing sophistication of his customers when it came to beer preferences, a more affluent customer base, and a willingness to pay higher prices for what was perceived as a better quality beer.

Wine sales nationwide were also increasing dramatically. A recent study by the Bureau of Labor Statistics revealed that beer-to-wine sales were 3.2-1 in 1982 and 1.2-1 in 2012 (Vo. 2012). However, at the Pub, the ratio was closer to the 1982 ratio of 3-1, beer to wine. Anecdotally, several customers, mostly women, had asked Jim if he could stock a wider variety of wines. Wait staff and bartenders also mentioned that female customers had asked about a greater selection of wines. This corroborated the fact that 80 percent of all wine sales in the U.S. were to women (Atkin, 2007)1 Jim suspected that men were also interested in an expanded wine offering, but most of the requests had come from women. These facts, along with the demographic changes in Jim’s customer base, had prompted him to consider featuring wine as well as craft beers at the Pub. While Jim had no trouble determining which craft beers to stock, neither he nor his father was comfortable when it came to selecting wines. Jim was in his late 50s, and his father was 86 years old, and thus they were in a different age demographic than the typical Selwyn Pub patron. Customer comments on wine ran the gamut of varietals and brands, providing little actionable data to use in his decisions.

Competition

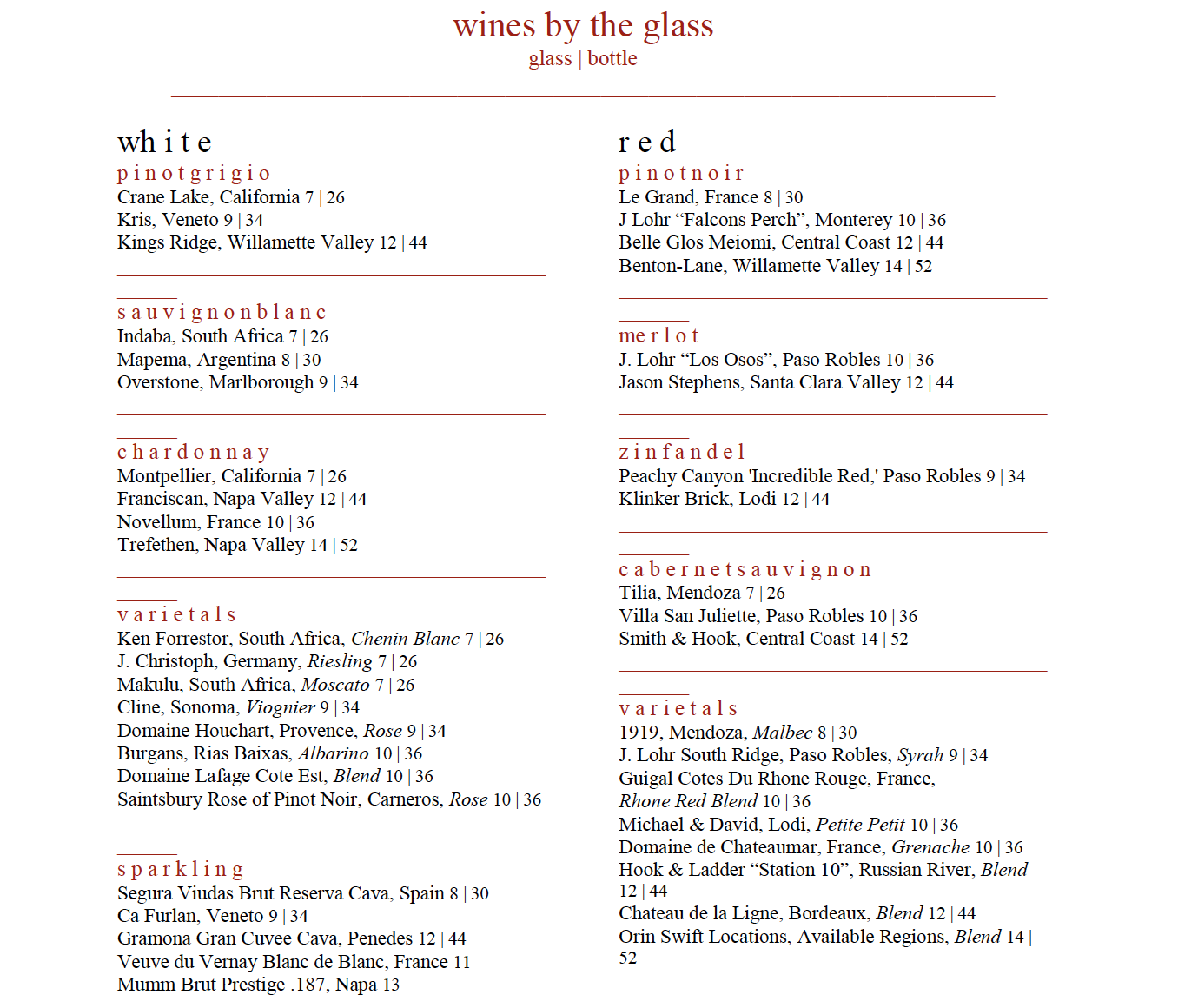

Within walking distance of the Pub, three establishments sold wine by the glass and bottle: Petite Philippe, Nolen Kitchen, and the Mellow Mushroom. Petite Philippe was strictly a wine bar focusing on higher-end wines along with specialty chocolates. It was owned and operated by a Level One Sommelier through the Court of Master Sommeliers and his wife, a pastry chef who had earned a Professional Chocolatier certification from the École Chocolat. The atmosphere in Petite Philippe was more of a wine cellar than a restaurant or pub, and bottles of wine were USD 50 and above. Petite Philippe featured wine tastings and chocolate pairings. Nolen Kitchen was a moderately priced casual dining restaurant featuring about 30 different wines served by the glass or bottle with bottle prices from USD 26 for a Pinot Grigio to USD 52 for a Cabernet Sauvignon. Appendix 1 shows the wine offerings and pricing at Nolen Kitchen.

The Mellow Mushroom was a franchise pizza restaurant catering to families; it had a full bar specializing in beer and mixed drinks with a couple of house wines by the glass. While all of these competed for customers with the Pub, none offered a pub-like experience, which was the hallmark of the Selwyn Pub. Jim believed that his closest competitor was Nolen Kitchen. Given its bottle pricing, he felt that to be competitive he needed to be somewhat below their prices on both glasses and bottles.

Selecting Wines

Initially, Jim relied on his knowledge of wine, which was somewhat limited, so he tended to choose popular brands such as Kendall-Jackson, Mondavi, and Beringer. Jim believed that these well-known and popular California wines were in keeping with a pub experience. At first, his selections seemed to be selling. Wine sales had nearly doubled in the first three months after the introduction of a larger wine selection. However, additional increases in wine sales did not materialize and total wine sales stalled. Wine revenue had leveled off at just 2 percent of total sales and 10 percent of alcoholic beverage sales. Jim wondered if it might have been his wine selections that had caused total wine sales to lag. Jim decided to ask his local wine distributor for help in choosing brands and varietals. The wine distributor was more than happy to bring Jim a selection of moderately priced, good quality wines that would be in keeping with a pub experience. The wines he brought with him were both reds and white, from domestic and international vineyards. As Jim tasted the different wines, it was clear that making choices was going to be tough. It was difficult for him to distinguish the quality of the wines. The selection offered by the distributor had wholesale prices that fell into three categories: under USD 10, USD 10 to USD 20, and above USD 20. Typical wine pricing in restaurants in Charlotte for wholesale bottle price per glass with approximately four glasses per bottle entailed a markup of about 300 percent on a bottle. In keeping with the Pub’s practice of providing customers with excellent value, he instructed his bartenders to offer a “heavy pour” of three glasses per bottle and reduced the contribution margin on bottles and glasses compared to his competitors. Even with the reduced margins and heavy pours, the contribution margin in dollars on a glass of wine was greater than domestic beer and craft beer. Jim had not yet done an analysis of the average customer bill, with and without wine, but, based upon the contribution margins, he expected the total bills to be higher with wine purchases. He had also noticed that customers were now buying a bottle of wine and taking what they did not consume home (the Pub’s license permitted customers to take an unfinished bottle home with them).

The distributor also brought a fact sheet, which included a description of each wine, a picture of the bottle, a rating, and a flavor profile. After sampling several of the distributor’s selections, Jim was still uncertain which wines to purchase. Jim felt that he was not knowledgeable enough to adequately evaluate the quality of each wine. He decided that the best way to make his selection was to rely heavily on the advice of the wine distributor. Not only did the wholesale prices vary considerably, but the labels were also from smaller, less well-known vineyards. Beyond choosing the right wines for the Pub, Jim worried that his existing wait staff would not be able to advise customers adequately to help them with their wine selections.

RESULT OF THE WINE EXPERIMENT

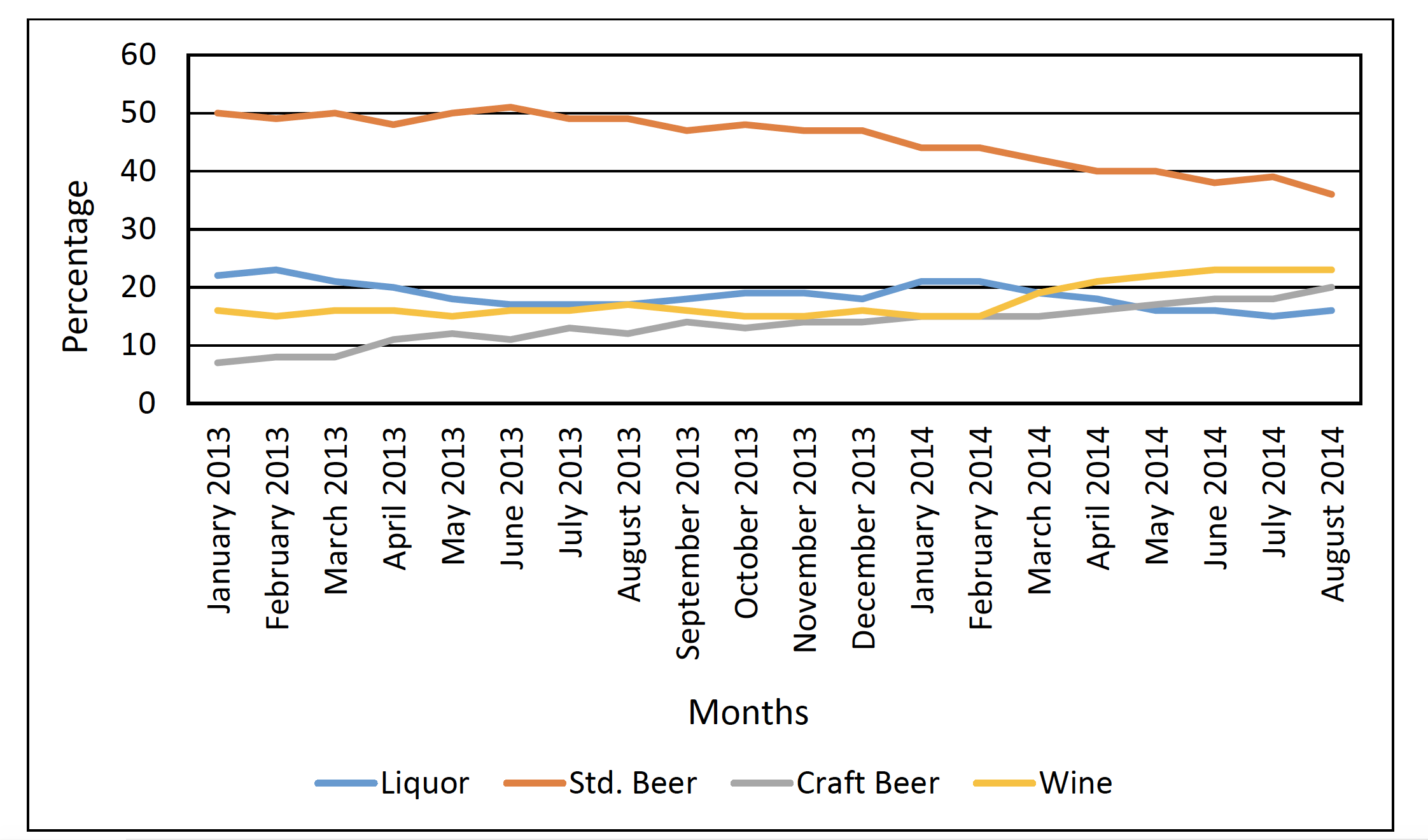

Jim decided to try an enhanced wine menu in March 2014. He started with a limited selection of six reds and six whites. The choice of wines was the result of recommendations from his distributor as well as his personal tasting of each of the wines. The distributor would visit the Pub regularly with new selections, and Jim would restock wines that had sold well and replace those not moving. Jim’s goal was to satisfy the customer desire for wine and, if possible, move the percentage of beverage sales of wine closer to the national average. He felt that as a pub, his sales would always be predominantly beer, but the recent trend in craft beer, as well as the increasing number of women frequenting the Pub, suggested that the market for a better wine selection could be significant. Interestingly, after the experiment with a wider selection of better wines began, Jim saw wine sales increase. Wine sales had grown from 16 percent of total beverage sales to 26 percent in just six months. The percentage of sales attributable to each beverage type for the period January 2013 to August 2014 is shown in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1. Percentage of Total Beverage Sales Attributable to Each Beverage Type

|

|

Liquor

|

National Beer

Brand

|

Craft Beer

|

Wine

|

Other

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

January 2013

|

21

|

51

|

7

|

16

|

5

|

|

February 2013

|

21

|

51

|

8

|

15

|

5

|

|

March 2013

|

21

|

49

|

9

|

16

|

5

|

|

April 2013

|

20

|

48

|

11

|

16

|

5

|

|

May 2013

|

18

|

50

|

12

|

15

|

5

|

|

June 2013

|

17

|

51

|

11

|

16

|

5

|

|

July 2013

|

17

|

49

|

13

|

16

|

5

|

|

August 2013

|

17

|

49

|

12

|

17

|

5

|

|

September 2013

|

18

|

47

|

14

|

16

|

5

|

|

October 2013

|

19

|

48

|

13

|

15

|

5

|

|

November 2013

|

19

|

47

|

14

|

15

|

5

|

|

December 2013

|

18

|

47

|

14

|

16

|

5

|

|

January 2014

|

18

|

47

|

15

|

15

|

5

|

|

February 2014

|

19

|

46

|

15

|

15

|

5

|

|

March 2014

|

19

|

42

|

15

|

19

|

5

|

|

April 2014

|

18

|

40

|

16

|

21

|

5

|

|

May 2014

|

16

|

40

|

15

|

24

|

5

|

|

June 2014

|

16

|

38

|

16

|

25

|

5

|

|

July 2014

|

15

|

39

|

15

|

26

|

5

|

|

August 2014

|

16

|

36

|

17

|

26

|

5

|

Source: The Selwyn Pub

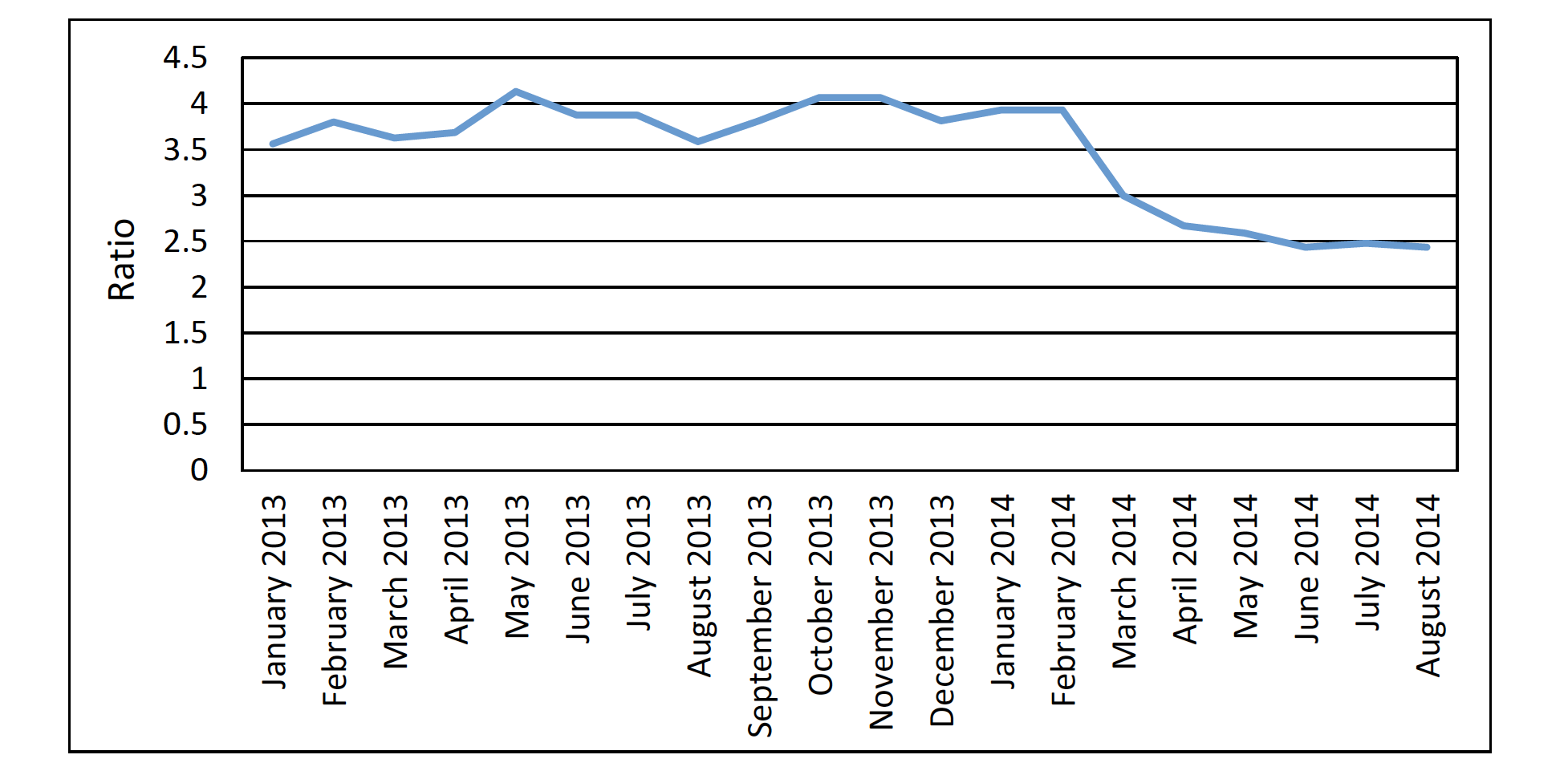

When the contribution ratio for each beverage type was considered (liquor=.66, national beer brands=.5, craft beer brands=.75, wine=.75, other=.75),2 increases in craft beer and wine were having a definite impact on his profit margin. Also, wine as a percentage of beer sales had moved closer to the national average of 1.2-1, one of Jim’s objectives. As can be seen in Exhibit 2, beer sales as compared to wine sales had gone from 3.5-1 to 2.5-1.

Exhibit 2. Ratio of Beer to Wine Sales

Source: The Selwyn Pub

Source: The Selwyn Pub

However, Jim noticed that the gains for wine were concentrated in the first three months of the trial with little or no gains in the last three months (shown in Exhibit 3). Jim wondered if the leveling off could be attributed to the fact that he had reached the right mix of beer to wine in the pub or some other factor.

![]() Exhibit 3. Beverages Sales by Category

Exhibit 3. Beverages Sales by Category

Source: The Selwyn Pub

Source: The Selwyn Pub

THE SELWYN PUB WAIT STAFF

At any given time, roughly 35 to 40 people worked at the Selwyn Pub, consisting of about 20 staff (including food runners, chefs, and waitstaff), four full-time bartenders, two part-time bartenders (who also served as waitstaff on a part-time basis), and four managers. The average tenure for full-time bartenders was four years while the wait staff often worked only seasonally. About 30 percent of the wait staff were full- and part-time students at the Queens University of Charlotte who juggled class schedules and internships alongside their shifts at the Pub. Roughly 10-25 percent (4-10) of the staff was under the age of 21 at any given time (North Carolina law allows individuals under 21 to serve beer and wine in restaurants). About half of the employees had other part-time or full-time jobs. During the early weekdays, two bartenders were on shift, one at the outside bar and the other on the inside; typically, three wait staff worked the restaurant during those timeframes. Toward the week’s end, four bartenders tended the bars and four to six wait staff worked the various tables. Up to three managers were on site at any one time depending upon the expected customer size.

Wait Staff Wine Knowledge

The staff was more familiar with the beers than with wine. In fact, to save time and avoid spillage, bottles of wine were opened by the bartenders and served to the customer uncorked. Employees who were more comfortable with the wine offerings drew upon their knowledge gained from their personal experiences as consumers rather than from any formal training. New additions to the wait staff underwent a two-day socialization and training period. During the first day, the employee who trained new hires introduced them to the menu, the layout of the Pub, and best practices in customer service; on the second day, the new wait staff members were trained on the computer system. No particular attention was given to wine beyond a brief discussion about the wine menu.

One of the employees, who split her time between waiting tables and bartending, explained that she and three other employees had attended a distributor sampling the previous summer involving a Gerard Bertrand Gris Blanc wine. Beyond that sampling, she did not recall attending others and was unaware of any other incidents of employees meeting with the Pub’s wine distributors. “The last staff meeting was about three months ago,” one staff member explained and further said,

It’s difficult getting everyone here at the same time in light of varying schedules and obligations outside of the Pub. . . At the meetings, we usually discuss how we can improve our interactions and provide better service to the customers. You know, helping others. When you see a customer seated in someone else’s section waiting, say hello and offer to get drinks.

She could not recall any discussion of wines as a strategic initiative during the staff meetings.

Employee Motivation

“We want to sell wine because our tip is based on the price of the bill. Wines are usually more expensive than beer, so more wine equals a bigger bill equals bigger tips,” offered a bartender. To complement the natural tip incentive, Jim occasionally held one-day or evening contests involving the sale of wines, with the winner receiving a bonus (e.g., USD 20). “Sure, some people get into it, particularly those who want money,” explained one employee. “But you have some people who are motivated while others just aren’t into pushing themselves in that way.” Employees were evaluated informally on general customer service ability and team play versus an evaluation of the employee’s performance against particular stated criteria (e.g., competencies or behaviors like effort expended to sell wine).

Wine orders were split roughly fifty/fifty between customers who ordered at the tables through wait staff and those who sat at the bar. A wait staff member stated that most staff simply offered the food and wine menu with no particular explanation about anything on it.

One of the bartenders explained,

We want Selwyn Pub to be like the Myers Park living room. Wine offerings are very consistent with this style and our customer base. I’ve been in the business for about 20 years now. I don’t drink wine and am not very familiar with it myself. It’s tough to sell something you don’t know much about, even though your commissions may increase.

THE DECISION

Jim was now six months into the wine experiment and fall was approaching. With university students returning to campus, milder weather, customers back from summer vacations, and the start of the football season, he needed to decide whether to continue to invest time and resource into growing wine sales at The Selwyn Pub, or refocus his efforts on more traditional beer and liquor sales.

ENDNOTES

1 Atkin, T., Nowak, L., & Garcia, R. (2007), Women wine consumers: information search and retailing implications..International Journal of Wine Business Research, 19(4), 327-339.

2 Contribution Ratio=Contribution Margin / Price Contribution Margin=Price-Variable Cost

REFERENCES

Atkin, T., Nowak, L., & Garcia, R. (2007), Women wine consumers: information search and retailing implications..International Journal of Wine Business Research, 19(4), 327-339.

Reichs, K. (1999). Death du jour. Scribner.

Trip Advisor (2013). http://www.tripadvisor.com/ShowUserReviews-g49022-d837778- r148965795-Selwyn_Avenue_Pub-Charlotte_North_Carolina.html. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

Vo, Lam Thuy. (2012). What America spends on booze. NPR.org. Report 2014. http://www.npr.org/blogs/money/2012/06/19/155366716/what-america-spends-on-booze

Appendix 1. Nolen Kitchen Wine Menu

Source:

Source: