Mary A. Barrett, Luca Gottardi, & Ken Moores

Date Accepted: February 17, 2018

Keywords: Vineyard Management, Financial Analysis, Grape Varieties, Strategy, Dupont Analysis, Family Business.

Brothers Lorenzo and Angelo Poncini are part of a family business in the Trentino region of northern Italy. It began as a trucking firm but diversified over the years. One such diversification is grape growing, which began in 1988. The Poncini family sends its grape harvest, currently Pinot Grigio, to a local cooperative, Gruppo Italiano Cantine, which makes and markets the wine. However, the vines the family originally planted – a major proportion of the planting surface – are getting past their prime and the quantity, if not the quality, of the family’s grapes will soon begin to decline.

Lorenzo and Angelo disagree about what strategy the family should use to respond to this situation. Lorenzo favors grubbing up the older vines and applying for EU subsidies to replant, perhaps even with a new grape variety, Glera, whose popularity has increased sharply in recent years, like the wine which it is used to make: Prosecco. Grubbing up and replanting would also create an opportunity to mechanize the harvest, which would reduce the cost of hand-picking in the future. Angelo sees things differently. While he recognizes that the vines are getting old he is reluctant to grub up hurriedly and even more so to rush into planting a new grape variety like Glera, whose market staying power is unproven.

The Poncini family business recently started using a family council to help it resolve family and business disagreements and, at the recommendation of Carlo, the oldest of the brothers, Lorenzo develops some strategic options to present to the council. The case requires students to adopt the position of an external member of the council and advise the family what it should do. As the Poncinis run a family business, the likely effects of each option on the family are as important as their financial effects.

It was December 2015 and two brothers, Carlo and Lorenzo Poncini, sat together at the long dining table of the family’s holiday house in the mountains. Carlo and Lorenzo were the oldest and the youngest, respectively, of the four children of Gianni and the late Arianna Poncini. Another brother, Angelo, and a sister, Emilia, were the middle siblings. Christmas was over and most members of the extended Poncini family had already left. Carlo and Lorenzo were almost ready to leave too. While the gathering had been cordial and full of the usual family jokes, there had been some tension in the air. Carlo decided to broach the issue with Lorenzo.

“It’s clear that you and Angelo don’t see eye to eye about our grape growing,” Carlo said. You think things should be done differently – grow a more lucrative grape variety and find savings by harvesting mechanically rather than by hand. Angelo is more cautious, and these ideas make him nervous. That’s understandable – he has been in charge of managing the vineyards for a long time. And there’s been a worldwide recession in the last few years while you’ve been studying, and our business has been affected, like everyone else’s. How can we be sure that things will work out the way you hope?”

Lorenzo said nothing, so Carlo continued. “Remember, we have a family council now.” He was referring to the fact that in the latter part of 2015, and with some difficulty, the Poncini family had begun to formalize its processes for making decisions about family and business matters. It now met regularly as a family – not including spouses – to try to talk things over instead of getting angry with each other. “So why don’t you and Angelo use the council to try to get an objective view of your ideas?” Lorenzo sighed and sat down at the dining table, which before the Christmas festivities had been the scene of a rather fiery family council meeting. “Yes, you’re right. But I don’t think Angelo is ready to listen. He can’t see beyond what we’ve always done, same old grapes, same old methods…,” Carlo remonstrated gently with Lorenzo. “Well, at least he agrees with you on one thing: a lot of our vines are getting old. And there’s no point in doing something new just for the sake of it. It has to be worthwhile for the family.”

Lorenzo picked up the financial documents the family had discussed at their council meeting. (See Exhibits 1 and 2). He shook his head as his eyes ran over the figures.

Exhibit 1. Condensed income statement for grape-growing operations 2010-2014 (in €)

|

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Revenues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pinot Grigio sales (older vineyard)

|

64,324

|

66,844

|

67,661

|

75,125

|

65,438

|

|

Pinot Grigio sales (newer vineyard)

|

19,945

|

28,461

|

21,799

|

34,282

|

29,262

|

|

TOTAL revenues

|

84,269

|

95,305

|

89,460

|

109,407

|

94,610

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Expenses

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Labor

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

. Pruning

|

10,836

|

11,518

|

9,554

|

9,182

|

12,487

|

|

. Cutting back buds

|

20,716

|

18,353

|

21,502

|

30,009

|

26,726

|

|

. Thinning out

|

708

|

0

|

3,459

|

2,270

|

857

|

|

. Harvesting

|

5,476

|

4,577

|

7,868

|

9,732

|

10,781

|

|

. Other (agricultural products, fertilizer, etc.)

|

5,847

|

4,318

|

1,873

|

5,497

|

4,779

|

|

Subtotal Labor

|

43,583

|

38,766

|

44,256

|

56,690

|

55,630

|

|

Salary (note 1)

|

29,603

|

26,488

|

26,988

|

27,306

|

27,478

|

|

Depreciation

|

7,491

|

6,971

|

4,841

|

3,715

|

7,389

|

|

Finance

|

269

|

270

|

870

|

908

|

1,492

|

|

Overheads (note 2)

|

4,187

|

4,040

|

6,856

|

8,603

|

7,233

|

|

Taxes & levies, allowances, services, misc.

|

1,829

|

1,010

|

3,583

|

2,184

|

3,920

|

|

TOTAL expenses

|

88,394

|

76,043

|

87,648

|

101,874

|

100,554

|

|

NET profit/loss

|

-4,118

|

19,278

|

2,066

|

10,001

|

-4,312

|

Exhibit 2. Statement of financial position for Poncini grape-growing operations 2010-2014 (in €)

|

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ASSETS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cash and bank

|

10,082

|

18,853

|

21,542

|

3,625

|

24,120

|

|

Accounts receivable

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

2,100

|

|

Prepaid expenses

|

215

|

348

|

72

|

0

|

626

|

|

Other current assets

|

139,917

|

173,046

|

152,635

|

213,439

|

200,035

|

|

Intangible assets

|

5,437

|

4,167

|

5,869

|

10,969

|

8,780

|

|

Machinery and equipment

|

30,150

|

38,014

|

40,306

|

45,049

|

45,433

|

|

Accumulated equipment depreciation

|

-6,030

|

-8,363

|

-11,052

|

-14,057

|

-17,138

|

|

TOTAL ASSETS

|

179,771

|

226,065

|

209,372

|

259,025

|

263,956

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LIABILITIES

|

|||||

|

Accounts payable

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

290

|

0

|

|

Accrued liabilities

|

3,346

|

3,145

|

3,080

|

2,573

|

1,870

|

|

Other liabilities

|

41,361

|

76,078

|

57,384

|

96,690

|

108,534

|

|

TOTAL LIABILITIES

|

44,707

|

79,223

|

60,464

|

99,553

|

110,404

|

|

|

|||||

|

SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Share capital

|

10,000

|

10,000

|

10,000

|

10,000

|

10,000

|

|

Contribution reserve

|

129,183

|

129,183

|

129,183

|

129,183

|

129,183

|

|

Other ordinary reserves

|

0

|

-4,119

|

7,659

|

10,288

|

18,681

|

|

Net profit/loss

|

-4,119

|

19278

|

2006

|

10001

|

-4,312

|

|

Shareholders' dividends

|

0

|

-7,500

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

TOTAL SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY

|

135,064

|

146,842

|

148,908

|

146,842

|

153,552

|

Lorenzo said, “I understand that. But there’s no disguising the fact that we made an operating loss in 2014!” Carlo interrupted him gently. “Well, it’s been tough for everyone in Trentino, not just us. As I said, maybe discussing it with the family council could give us all a fresh perspective. Why don’t you present some options at the next meeting? It’s December now, and I know you would like to implement your ideas at the next harvest, but we should get our council’s insights first. I can call a meeting in a few days, if you like.”

As the youngest family member and having only recently finished his studies, Lorenzo appreciated Carlo asking for his ideas. Angelo, on the other hand, had been annoyed when Lorenzo drew attention to the net loss from the family’s grape growing in 2014. Lorenzo felt Angelo was getting impatient with what he perceived as criticism from his kid brother. That was the trouble with being a family business, Lorenzo thought. You could never really keep family and business decisions apart…

THE ITALIAN WINE INDUSTRY

The variety of Italian wine is appreciated worldwide, and Italy’s wine-producing regions are among the oldest in the world. Italy also produces the largest amount of wine by volume of any country: about 45-50 million hectolitres per year, about one-third of the world’s production (European Commission, 2016). As well as being exported around the world, Italian wine is extremely popular in Italy. Italians are the fifth largest group of wine consumers in the world by volume.

Wine has always been subject to a high level of regulation in terms of both its method of production and nomenclature, e.g. its place of origin. The various types and levels of wine regulation are shared between various levels of the Italian government and the European Union (EU), and there are changes from time to time in terms of which body regulates what. The distinctions between specific ways of describing Italian wines are complex. To take Prosecco DOC as an example, the acronym DOC refers to the Controlled Designation of Origin (DOC) status of the Prosecco wine style. This means the wine must comply with very strict rules in a specific geographical area which is historically renowned for its Prosecco production. The environmental conditions of the area, such as soil characteristics and climate, give it its characteristic qualities. The DOC appellation adds considerably to the prestige and thus the price of the wine. The term Denomination of Controlled and Guaranteed Origin (DOCG) is an even more tightly controlled (and therefore even more prestigious) wine designation. In 2008 the EU formally abolished the distinction between DOC and DOCG in favor of PDO (Protected Designation of Origin). However, the greater value attached to DOCG meant that Italian growers and wine-makers did not want to abandon the DOC/DOCG distinction, so they continue to use both terms (Italian Wine Central, 2014).

Italian wine production is highly fragmented in terms of both vineyard size and the number of farms, leading to grape growing virtually everywhere in Italy. In 2014 almost 390,000 farms had vineyards; their average area was only 1.7 hectares. Twenty-nine percent of the vine area was managed by 69 percent of the farms, which were less than 5 hectares each. Farms larger than 20 hectares were only 7 percent of the total, but managed 33 percent of the national vine area (See Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3. Number of farms and total vine hectares by farm size

|

|

No. of farms

|

Hectares

|

|---|---|---|

|

Farm size

|

|

|

|

0.01–0.99 ha

|

90,829

|

26,062.44

|

|

1–1.99 ha

|

75,313

|

44,607.46

|

|

2–2.99 ha

|

47,673

|

44,294.61

|

|

3–4.99 ha

|

55,728

|

76,753.31

|

|

5–9.99 ha

|

57,686

|

128,299.02

|

|

10–19.99 ha

|

34,474

|

124,464.01

|

|

20–29.99 ha

|

11,444

|

59,282.91

|

|

30–49.99 ha

|

8,444

|

56,294.14

|

|

50–99.99 ha

|

4,926

|

48,912.31

|

|

More than 100 ha

|

2,364

|

55,325.97

|

|

|

||

|

Total

|

388,881

|

664,296.18

|

Both the number of Italian wine farms and the total land area used for viticulture have decreased greatly since the early 1980s, yet over the same period the areas intended for protected designation of origin (PDO) products have increased (See Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4. Number of farms and vineyard hectares in Italy 1982-2010

|

|

Census year

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

2010

|

2000

|

1990

|

1982

|

||||

|

|

Farms

|

Vine (ha)

|

Farms

|

Vine (ha)

|

Farms

|

Vine (ha)

|

Farms

|

Vine (ha)

|

|

Total vine area

|

388,881

|

664,296

|

791,091

|

717,334

|

1,184,861

|

932,957.04

|

1,629,260

|

1,145,097

|

|

Vine area for PDO production

|

124,970

|

320,859

|

108,711

|

233,522

|

92,590

|

190,852

|

105,019

|

209,794

|

|

Total % of PDO vines

|

32.14

|

48.30

|

13.74

|

32.55

|

7.81

|

20.46

|

6.45

|

18.32

|

Source: Istat, Agricultural Census 1982, 1990, 2000, 2010.

There are two groups of wine producers: the thousands of small farms producing small amounts of wine (often for their own consumption) and highly professional farms which produce high volumes of wine. There are clear differences among the two groups in terms of production costs, level of vertical integration of the production process, relationship with the market, and production philosophy. This leads to a strong fragmentation of the wine production process, resulting in a reduction of the value accruing to grape growers.

As evidence of this fragmentation, Italy has a very high number of establishments which process grapes into wine (Malorgio et al., 2011). They are of three types: farm-based wineries, which convert grapes produced on the farm and purchased on the market; industrial wineries, which process wine grapes exclusively purchased on the market; and cooperatives, which process their members’ grapes but also grapes purchased on the market. Cooperatives account for the bulk of wine production, but farm wineries are the most numerous even though they are smaller in size and produce less wine. In addition to wine processing establishments there are also numerous bottlers since bottling is often not economically feasible for small farm-based wineries.

Gori and Sottini (2014) point out that the end result of this high level of specialization of the Italian wine production sector is strong fragmentation of the supply. With the exception of large-scale enterprises that can vertically integrate the production process and reach the final market directly, farms are not able to work together. As a result, farms are price-takers, who find it difficult to achieve fair returns for their production inputs. Cooperatives aim to mitigate this problem by negotiating prices on behalf of their member farmers in a particular location and marketing the location’s wines.

THE HISTORY OF THE PONCINI FAMILY AND ITS BUSINESSES

Lorenzo, Angelo, and Carlo were members of the third generation of the Poncini family-in-business. See the genogram in Exhibit 5.

Exhibit 5. The Poncini family

Ernesto Poncini (d. 1976)

m. Ursula Galli (d. 1974)

╓─────────────╥─────╨─────╥───────────╖

Gianni (b. 1933) Nicola Rocco Mia

m. Arianna Santoro

(b. 1949, d. 2010)

╟───────────╥───────────╥───────────╖

Carlo (b. 1972) Angelo (b. 1974) Emilia (b. 1977) Lorenzo (b. 1981)

m. Marianna m. Maria partner: Massimo

╓───────────╫───────────╖

Damiano (b. 2000) Isabella (b. 2002) Marco (b. 2011)

Ernesto, Lorenzo’s grandfather, started the business the business in 1949 when he bought the first truck in Cembra, a poor village in the valley of the same name close to Trento[1]. The truck eventually replaced the two horse-drawn carts Ernesto had used to carry produce and liquor between the city of Trento and the surrounding valley. Within a few years, Ernesto and his wife Ursula acquired an employee and another truck to take advantage of growing transport links outside the Cembra area and the development of wood and porphyry production. (Porphyry is a hard, decorative stone used in building.)

In 1957, Ernesto moved his family moved to Trento and bought a large property on Dosso Dossi Street which was big enough to accommodate himself, Ursula and his siblings and their families. The property had a large space at the back where Ernesto stored and maintained his trucks himself, allowing him to save money. The family began to invest in property, and at the time this case was written, they owned 15 flats. However, not all was well. As a consequence of conflicts between Ernesto and his sons Rocco and Nicola, and to some extent Mia, the family decided to dissolve the truck business, which in 1967 comprised six trucks. In 1968 Gianni, with support from Ernesto and Ursula, opened his own transport company: Gianni Poncini Trasporti. The new company had just one truck. Ursula managed the back office of the new company as well as the original firm.

The new business expanded. Gianni’s much younger wife, Arianna, helped with its management, just as Ursula had with Ernesto’s firm. However, conflicts between Gianni and his siblings continued and in 1977 Gianni and Arianna moved away from Dosso Dossi Street, buying a piece of land in the countryside where they built a house and premises for their truck company. Later that year a second company was established: SAPG Autotrasporti, also managed by Arianna. The 1970s also saw the construction of a block of 10 flats in the nearby district of Canova; for many years the rentals from this property financed other family business projects. In 1981 the family purchased more trucks.

The Poncinis started growing grapes in 1988 after Gianni inherited two cornfields from some distant cousins. Gianni converted these cornfields, totaling 4.84 hectares in the nearby province of Vicenza in the Veneto region, into vineyards. He planted them with Pinot Grigio using the pergola vine-training method (See Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 6. Grape-growing in Veneto using pergola vine-training method

Source: Ilares Riolfi via WikiCommons

Source: Ilares Riolfi via WikiCommons

This method was well suited to Veneto’s sloping terrain and yielded good quality grapes, but it had the disadvantage of not allowing mechanical harvesting. The grapes were always hand-picked, which cost more and preserved the grapes’ quality better than mechanical harvesting. Later (See Exhibit 7) Gianni bought more land nearby on which he also planted Pinot Grigio, but this time used the Guyot method of vine training, which is compatible with mechanical harvesting (For a view of the Guyot approach, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eO_zyG5BGTg).

The second land purchase brought Gianni’s total grape-growing area to 7.3 hectares, considerably more than the average family-owned vineyard which was less than one hectare. Nevertheless, the Poncinis were not in a position to impact the wine market on their own. Joining together with other farmers and sending their grapes to the nearby cooperative, Gruppo Italiano Cantine (GIC), meant they could benefit from GIC’s brand strength and reputation for quality wines grown on Veneto’s steep slopes. GIC was founded in 1858 and became a co-operative in 1948. Since the mid-1980s, it had taken a leadership role in the region’s wine industry, increasing production quality and developing market awareness of the ‘terroir’ (special soil and climate qualities) of each local viticultural area.

Exhibit 7. Map of the Veneto region and its provinces

Source: Wikipedia Commons.

Source: Wikipedia Commons.

Grape growing was not the last of the Poncini business’s diversifications. In 1996 at the age of 63 Gianni acquired the retail outlet Porospan 2000 which sold construction tools and materials. This activity, along with grapes and property investments, gave further financial support to the Poncini firm’s activities. Gianni also established a new company, Immobiliare 2000, which mainly served as a ‘shell company’ to Poncini Autotrasporti, renting premises to it, paying the interest on its debts, and generally serving as a barrier against any financial problems. These were not long in coming: by 2005 Poncini Autotrasporti had started to lose money as a result of a dramatic increase in competition. At the time of writing the case, the Poncini Autotrasporti bank account was overdrawn to the extent of EUR 115,000 from a limit of EUR 120,000.

In the first decade of the 21st century, Gianni’s children’s paths in life were starting to become clear. Carlo and Angelo had studied accounting at high school and entered the trucking business straight from high school, Carlo on the transport side and Angelo in management. Emilia also entered the family business after graduating high school in 2000, working in Poncini Autotrasporti as a secretary and then setting up and managing its computer systems. Lorenzo, unlike the others, did university study, focusing on economics, including the economics of wine.

The family had a high propensity for conflict. Ursula had died in 1974 and Ernesto died intestate in 1976. All four of Ernesto’s children argued among themselves over the inheritance, especially the property at Dosso Dossi Street. The dispute ended only in 2002 when Rocco, ill and in debt, sold his share of the property to Gianni. Gianni, after selling some flats to finance the purchase, owned a majority share of the Dosso Dossi Street property and formally transferred this asset to his children. This dispute was resolved, but others arose between Gianni and various members of Arianna’s family. One dispute, over the leadership of a stone-crushing company Gianni had established with some of Arianna’s relatives, affected Poncini Autotrasporti. Carlo (via Poncini Autotrasporti) had bought shares in the new company, but it failed to thrive and Carlo had to sell the shares at a loss. This event hit Poncini Autotrasporti hard, because the company was already suffering the effects of increased competition. But Gianni, who was proud of Poncini Autotrasporti, always said he “could not understand how Carlo could lose money on it.” The disputes affected other family members. Emilia, for example, found it impossible to continue working for Poncini Autotrasporti against the background of so much conflict, and in 2006 she took a new job away from the family business. Despite the arguments, everyone – or at least those who were not actively involved in disputes – helped manage the vineyards, especially during the harvest.

Towards the end of the first decade of the 2000s, Arianna was diagnosed with cancer. The family started to investigate cancer and its causes and to change some aspects of their lifestyle, and this resulted in a change to how they grew grapes. In Lorenzo’s words:

We [the family as a whole] found out that the environment and what you eat may play a role. So, we changed our eating habits and began using more natural and eco-friendly farming practices in the vineyards. We wanted to leave better grapes and a better environment to future generations. It took a long time and a lot of money and hard work, but at the end of 2013 our vineyards were certified organic. […] Because our grapes are organic, GIC pays us a 20 percent price premium because a small proportion of consumers are willing to pay one or two euros more per bottle for a reasonably good organic wine, say EUR 10 for a bottle that would otherwise cost EUR 8. We supply only about 4 percent of GIC’s grapes by volume, but we supply 94 percent of their organic grapes.

In 2010 at the age of 60, Arianna died. This had a strong impact on the family. Lorenzo said in 2015:

She [Arianna] was such a calming influence on the whole family, which meant we had fewer family and business conflicts. It was so strange that she should die before my father, despite being so much younger. We still feel lost without her. And we don’t always keep our tempers when we have business disagreements.

Arianna had managed many of the Poncini family’s business activities, and after her death they were reorganized. A summary of developments in the business after Arianna’s death follows.

TRANSPORT Carlo became CEO and the sole owner of Poncini Autotrasporti by buying out all the other shareholders; Gianni was nominated chairman. Carlo then went into two external partnerships. With the first partner in 2012 he opened a second truck company, Ecotrasporti Poncini, whose main activity was the transportation of waste. Carlo and the partner were the shareholders, and the partner helped Carlo get the necessary permits. Carlo thought the new business would be more profitable and have fewer competitors than the original truck business. However, the new company registered a major loss in its first year and the partner left at the beginning of 2013. Carlo merged Ecotrasporti with Poncini Autotrasporti and hired a consultant in business finance and auditing, but this person also left after six months without making significant changes. Lorenzo and Angelo agreed to mortgage some flats to help Carlo out, but the bank was still reluctant to lend more money to the truck company.

CONSTRUCTION RETAIL Porospan 2000 closed in 2012 when the brick manufacturing company which supplied it went bankrupt. Angelo and his wife Maria later restarted the firm as a separate entity from the family business, under the name Porospan, with Angelo as CEO.

PROPERTY Lorenzo had obtained a qualification in property management and began managing the two property businesses, Immobiliare Poncini and Immobiliare 2000, and the apartments in Canova. Angelo helped with this when Lorenzo was preoccupied with study.

GRAPE GROWING Carlo, Angelo, Emilia, and Lorenzo were equal shareholders in the grape-growing business with Angelo as CEO. Angelo, who was formally registered with GIC as the farmer, represented the Poncini family in its dealings with the cooperative.

GOVERNANCE In 2011, at the age of 78, Gianni decided to step down as head of the family firm, and passed his properties and company shares to his children. In the following few years his health began to decline. In 2015 the family began having semi-formal meetings where they discussed family and business matters.

A timeline summarizing the development of the Poncini family business is at Exhibit 8.

Exhibit 8. Timeline showing the development of the Poncini family’s businesses

|

Year

|

Event

|

|---|---|

|

1949

|

Ernesto Poncini buys the first truck in Cembra, marking the start of the family business.

|

|

1955

|

Ernesto sells his carts, buys second truck.

|

|

1957

|

Ernesto buys a large property in Dosso Dossi Street in Trento to accommodate himself, his family, his extended family, and to provide space for the trucks. Begins investing in property.

|

|

1967

|

Ernesto’s trucking company closes following disputes with his sons Rocco and Nicola.

|

|

1968

|

Gianni, Ernest’s third son, starts his own transport company (Poncini Autotrasporti).

|

|

1970s

|

Flats constructed in Canova.

|

|

1987

|

Gianni inherits 4.84 hectares of cornfields in Veneto and converts them to vineyards.

|

|

1988

|

Gianni plants the cornfields with Pinot Grigio grapes, using the Trentino Pergola vine training system. This system is not compatible with mechanical harvesting.

|

|

1989

|

Carlo finishes high school and joins the family firm. His main interests center on the trucking side of the business.

|

|

1993

|

Angelo finishes high school and joins the family firm. He also works in the trucking side of the business but is also formally registered as the farmer, in which role he manages the grape-growing operations.

|

|

1996

|

Beginning of construction retail business (Porospan 2000), managed by Angelo. Its most successful product is aerated bricks.

Emilia graduates from high school and joins the family business. She begins overhauling its information management processes.

|

|

2000

|

Establishment of new property management company, Immobiliare 2000, which acts as a shell company to Poncini Autotrasporti.

|

|

2001

|

Gianni buys an additional 2.46 hectares, plants more Pinot Grigio grapes, but using a different vine-training system, Guyot, which facilitates mechanical harvesting.

|

|

2002

|

Immobiliare Poncini, a subsidiary of Immobiliare 2000, is formed to facilitate the transfer of the Dosso Dossi Street property to Gianni’s children.

|

|

2004

|

Gianni starts a stone-crushing company with Vincenzo, one of his brothers-in-law, and Poncini Autotrasporti buys shares in the company. However, Gianni and Vincenzo quarrel, and Gianni eventually leaves the stone-crushing business. Poncini Autotrasporti’s shares in the stone-crushing company are sold at a loss, leading to some ill-feeling between Carlo and Gianni.

|

|

2006

|

Emilia, upset by ongoing family conflict, takes a job outside the family firm.

|

|

2008

|

Arianna is diagnosed with cancer.

|

|

2010

|

Arianna dies. The family adopts a healthier lifestyle and begins investigating organic methods of grape growing.

Lorenzo begins managing the family’s rental properties, assisted by Angelo.

|

|

2011

|

Gianni formally steps down and Carlo becomes CEO.

|

|

2012

|

Porospan 2000 closes, later reopens as a separate entity, Porospan, with Angelo as CEO. Poncini Autotrasporti experiences financial difficulties. Carlo diversifies into waste transportation by establishing Ecotrasporti Poncini. Poncini Ecotrasporti and Poncini Autotrasporti merge, but the company’s financial difficulties continue.

|

|

2013

|

The Poncini vineyards attain organic certification, one of very few vineyards in the region to have done this.

|

|

2015

|

Lorenzo completes his graduate studies. He does not have a formal role in the family business beyond his current responsibilities of managing the family’s rental properties.

The Poncini family begin regular council meetings to consider family and business issues.

|

As Lorenzo and Carlo drove back to Trento, Lorenzo was quiet, his mind preoccupied with how to present his ideas to present to the family council. In the quiet of his flat in the Dosso Dossi street house, he opened a computer folder. First, he checked production data for Italy’s most popular grape varieties (See Exhibit 9).

Exhibit 9. Italian production levels of the top 15 varieties of wine and table grapes 2014-2015 (in tonnes)

|

Variety

|

2014

|

2015

|

|---|---|---|

|

Pinot Grigio G.

|

16,186,244

|

11,407,364

|

|

Glera B.

|

2,526,757

|

15,445, 261

|

|

Sangiovese N.

|

8,532,571

|

19,905,485

|

|

Chardonnay B.

|

7,248,348

|

8,648,876

|

|

Merlot N.

|

4,911,540

|

5,256,965

|

|

Primitivo N.

|

4,514,275

|

5,489,937

|

|

Moscato Bianco B.

|

4,066,502

|

5,3044,367

|

|

Catarratto Bianco Lucido B.

|

6,417,308

|

4,465,247

|

|

Trebbiano Toscano B., Biancame B.

|

5,182,955

|

4,453,494

|

|

Sauvignon B.

|

3,167,334

|

3,439,148

|

|

Syrah N.

|

2,822,629

|

3,102,387

|

|

Barbera N.

|

3,099,733

|

3,054,394

|

|

Cabernet Sauvignon N.

|

3,472,844

|

3,007,696

|

|

Cannonau N., Tocai Rosso N., Alicante N.

|

2,660, 441

|

2,751,538

|

|

Vermentino B. Pigato B., Favorita B.

|

2,355,077

|

2,782,035

|

Source: Adapted from Il Corriere Vinicolo 33, pp. 5, 7.

As Lorenzo saw it, Pinot Grigio – the grape the family had planted – was still a very popular grape among Italian producers. However, a new varietal, Glera (See Exhibit 10), had gained popularity quickly over the last several years. While Pinot Grigio had long been the flagship of Italian grape varieties, Glera was different: back in 2002, it had ranked only thirtieth in terms of production volume. It was an excellent grape for Prosecco wine, for which the Veneto region was famous. Glera was one of the most ancient of the approximately 2,000 wine grape varieties in Italy; it attained high sugars (about 25 percent, while grapes in Champagne (Champagne wine was Prosecco’s main competitor) had at most 17 percent to 20 percent). Yet it still retained high acid levels, which were essential to a balanced sparkling wine. It was also intensely aromatic. Producers were trying to increase its quality even further by improving vineyards and wine-making methods (Consorzio de Tutela della DOC Prosecco, n.d.).

Exhibit 10. Growing Glera grapes in Veneto

(Note the wide spaces between the rows of vines, which allow for mechanical harvesting.)

Source: Paul Barker Hemings, via WikiCommons

Next, Lorenzo looked at figures about the subsidies Italian grape-growers had received for restructuring their vineyards (e.g. changing from one grape variety to another) and improving their growing methods (See Exhibit 11).

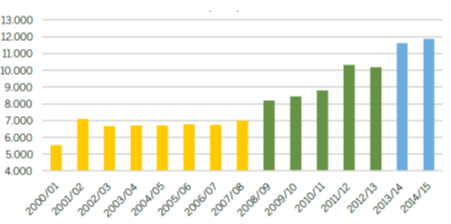

Exhibit 11. EU support for vineyard restructuring and conversion in Italy: Average paid per hectare per year (in €)

Source: Il Corriere Vinicolo 33, 2.

Source: Il Corriere Vinicolo 33, 2.

Lorenzo noted from the table that there were subsidies available from the European Union via the Italian Ministry of Agriculture for farmers who wanted to restructure their vineyards. On average they had been increasing: in 2014/15 successful applicants had been subsidized at an average of EUR 11,740 per hectare (see the second bar chart in Exhibit 11). In 2012 the Veneto region had issued an official bulletin – a 15-page document filled with a great deal of complex legal language – about the EU’s goals in vineyard restructuring and the criteria that farmers seeking subsidies had to meet. Lorenzo had not studied this document in detail, but he knew that subsidies were granted only for one or more of the following activities: a) relocation of vineyards, and b) improvements to vineyard management techniques (not just normal renewal of old vineyards). Producers were only compensated for loss of revenue directly due to the activity; and subsidies were intended to contribute to the costs of restructuring/conversion, not cover the total cost. Lorenzo had discussed the subsidies available in Veneto with a farmer there who owned 3 hectares of vineyards. A few years ago, that farmer had been granted a conversion subsidy of EUR 36,000, EUR 12,000 for each hectare to be grubbed up and restructured. “What I want to do is similar to what he did,” Lorenzo said to himself, “namely grub up our old vines, plant a new grape, Glera, using a better vine-training system, and harvest more efficiently. I think the Ministry of Agriculture will look on this favorably. But will the family council look on it favorably? I’ll need to argue my case. Time to do the figures…”

THE FAMILY COUNCIL MEETING

A few evenings later after dinner, the family gathered together again, this time in the living room at Dosso Dossi street. The atmosphere was warm, but thoughtful rather than jovial. The council assembled and like most councils of family firms in Italy consisted entirely of family members, until that evening. In deference to the importance of the issue to be discussed and the tension between Lorenzo and Angelo, Carlo and Gianni had invited a new person, Luigi Graciotti, to join the council. The Poncinis knew and respected Luigi, a farmer from the neighboring valley, for his grape-growing skill and reputation for looking at difficult decisions objectively. At the same time, as the owner of a family business, Luigi also understood the family dimensions of business problems.

Once pleasantries were over and everyone had a glass of wine handy, Carlo invited Lorenzo to present his ideas. Lorenzo had improvised a projector and screen on the living room wall. He also handed out a paper version of the slides he would show. The first pages were the profit and loss statement and statement of financial position that had been discussed at the meeting just before Christmas. Lorenzo stood up and turned to his audience. He first thanked Carlo for inviting him to present his ideas and explained that he had used the family’s financial data for 2010-2014 to ‘model’ four scenarios corresponding to four strategic options for managing the vineyards. He had also used the following information Angelo had given him about revenues from the old vineyards over the last five years (See Exhibit 12).

Exhibit 12. Revenues per hectare for Pinot Grigio 2010-2014 (in €)

|

Year

|

Hectares of Pinot Grigio

|

Revenues per hectare

|

Total revenues

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

2014

|

4.84

|

13,505

|

65,348

|

|

2013

|

4.84

|

15,525

|

75,125

|

|

2012

|

4.84

|

13,983

|

67,661

|

|

2011

|

4.84

|

13,814

|

66,844

|

|

2010

|

4.84

|

13,293

|

64,324

|

|

|

|

Average revenues per hectare 14,024

|

Average total revenues

67,860

|

Source: The Poncini family

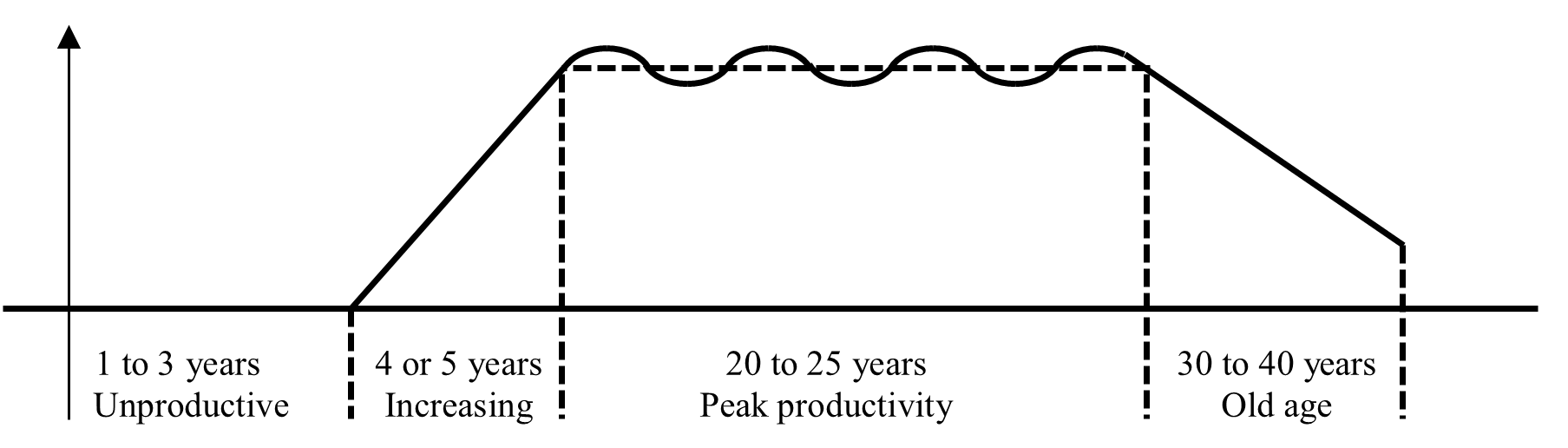

He began to speak in earnest. “Angelo and I agree that our older vineyards – the 4.84 hectares of Pinot Grigio which were planted in 1988 – will soon be past their best. This is nothing unusual, it happens to all vines eventually.” Lorenzo projected the diagram in Exhibit 13 below.

Exhibit 13. The life cycle of a grapevine

Source: Adapted from Fregoni (1988). Text translated by the authors.

“What we don’t know is how quickly the Pinot Grigio harvest will decline. Let’s consider Scenario 1. If, beginning in 2015, our Pinot Grigio declines by 5 percent a year, our revenues can be expected to decline by a similar amount. Scenario 1 shows this: revenues of EUR 65,348 in 2014 have declined by 5 percent to EUR 64,467 in 2015, by a further 5 percent in 2016, and so on. Our labor expenditure (pruning, cutting back buds, thinning out, and harvesting) will not change much, and I have allowed for a realistic increase in the wages we will need to pay. If the ‘old’ Pinot Grigio grape harvest declines that quickly, and GIC pays us on average the same as in the past five years, our net profit will be negative by 2021. And what about the rewards to us as a family? We haven’t often taken dividends, but it is reasonable for us to want to benefit from our grape growing.

Let’s assume that, in any year that we make a net profit, we distribute an amount equal to 60 percent of net profit as dividends. Under Scenario 1, we would distribute a total of EUR 49,860 in dividends.” Scenario 1 is reproduced at Exhibit 14.

Exhibit 14. Scenario 1: No replanting, ‘Old’ Pinot Grigio grape harvest declines at 5 percent per year Projected income statement 2015-2023 (in €) (condensed)

|

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

2019

|

2020

|

2021

|

2022

|

2023

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Revenues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pinot Grigio sales (old vineyards) (note 1)

|

64,467

|

61,074

|

57,681

|

54,288

|

50,895

|

47,502

|

44,109

|

40,716

|

37,353

|

|

TOTAL revenues

|

64,467

|

61,074

|

57,681

|

54,288

|

50,895

|

47,502

|

44,109

|

40,716

|

37,353

|

|

Expenditures

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Labor (see note 2)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

. Pruning

|

10,715

|

10,823

|

10,930

|

11,037

|

11,144

|

11,251

|

11,358

|

11,465

|

11,573

|

|

. Cutting back buds

|

23,461

|

23,696

|

23,930

|

24,165

|

24,400

|

24,634

|

24,869

|

25,103

|

25,338

|

|

. Thinning out

|

1,559

|

1,574

|

1,590

|

1,606

|

1,621

|

1,637

|

1,652

|

1,668

|

1,684

|

|

. Harvesting

|

8,302

|

8,225

|

8,148

|

8,071

|

7,994

|

7,917

|

7,841

|

7,764

|

7,687

|

|

TOTAL expenditures

|

43,422

|

43,856

|

42,291

|

45,159

|

45,159

|

43,593

|

46,028

|

46,462

|

46,896

|

|

NET profit/loss

|

21,045

|

17,218

|

13,391

|

9,563

|

5,736

|

1,909

|

-1,918

|

-5,746

|

-9,573

|

Note 1: To facilitate comparison, this condensed statement shows only the ‘old’ vineyards, as grubbing up and replanting (Scenarios 3 and 4) are not proposed for the ‘new’ vineyards.

Note 2: Costs for pruning, cutting back, thinning out, and harvesting are based on the average for expenditure for each item in the past five years plus an annual increase of 1 percent.

Related changes to balance sheet (in €) (condensed)

|

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

2019

|

2020

|

2021

|

2022

|

2023

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total Assets (note 1)

|

271,297

|

278,924

|

286,552

|

294,179

|

301,806

|

309,433

|

317,060

|

324,687

|

332,315

|

|

|

Total Liabilities

|

109,327

|

110,067

|

112,367

|

116,169

|

121,502

|

128,365

|

137,920

|

151,293

|

168,494

|

|

|

Shareholders’ Equity

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Net profit

(from table above)

|

21,045

|

17,218

|

13,319

|

9,563

|

5,736

|

1,909

|

-1,928

|

-5,746

|

-9573

|

|

|

Shareholders’ dividends

(note 2)

|

-12,627

|

-10,331

|

-7991

|

-5,738

|

-3,442

|

-1,145

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

Total

41,274

|

|

Total Shareholders’ Equity

|

161,970

|

168,857

|

174,185

|

178,010

|

180,304

|

181,068

|

179,140

|

173,394

|

163,281

|

|

Lorenzo paused. Everyone nodded, indicating that they understood his explanation so far. “Let’s turn to Scenario 2,” Lorenzo said (See Exhibit 15).

Exhibit 15. Scenario 2: No replanting: Old Pinot Grigio grape harvest declines at 2.5 percent per year Projected income statement 2015-2013 (in €) (condensed)

|

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

2019

|

2020

|

2021

|

2022

|

2023

|

|

Revenues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pinot Grigio sales

(old vineyards)

(note 1)

|

24,723

|

23,257

|

21,756

|

20,222

|

18,654

|

17,052

|

15,416

|

13,747

|

7,836

|

|

TOTAL revenues

|

24,723

|

23,257

|

21,756

|

20,222

|

18,654

|

17,052

|

15,416

|

13,747

|

7,836

|

|

Expenditure

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Labor (note 2)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

. Pruning

|

10,725

|

10,823

|

10,930

|

11,037

|

11,144

|

11,251

|

11,358

|

11,465

|

11,573

|

|

. Cutting back buds

|

25,338

|

25,103

|

24,869

|

24,634

|

24,400

|

24,165

|

23,930

|

23,696

|

23,461

|

|

. Thinning out

|

1,576

|

1,561

|

1,546

|

1,532

|

1,517

|

1,503

|

1,488

|

1,473

|

1,459

|

|

. Harvest

|

8,302

|

8,225

|

8,148

|

8,071

|

7,994

|

7,917

|

7,841

|

7,764

|

7,687

|

|

TOTAL expenditure

|

43,322

|

43,755

|

44,189

|

44,622

|

45,055

|

45,488

|

43,922

|

44,355

|

44,788

|

|

NET Profit/Loss

|

22,842

|

21,357

|

19,838

|

18,285

|

16,698

|

15,077

|

13,422

|

11,734

|

5,804

|

Note 2: Costs for pruning, cutting back, thinning out, and harvesting are based on the average for cost for each item in the past five years plus an annual increase of 1%.

Related changes to balance sheet (in €)

|

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

2019

|

2020

|

2021

|

2022

|

2023

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total Assets

(see note 1).

|

271,366

|

279,063

|

286,759

|

294,455

|

302,152

|

309,848

|

317,545

|

325,241

|

332,937

|

|

|

Total Liabilities

|

104,497

|

102,891

|

101,885

|

101,492

|

101,727

|

102,603

|

104,133

|

98,082

|

97,942

|

|

|

Shareholders’ Equity

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Net profit

(from table above)

|

22,842

|

21,357

|

19,838

|

18,285

|

16,698

|

15,077

|

13,422

|

11,734

|

5,804

|

|

|

Shareholders’ dividends

(see note 2).

|

14,834

|

13,954

|

13,054

|

12,133

|

11,192

|

10,231

|

9,250

|

8,248

|

4,702

|

Total

97,598

|

|

Total Shareholders’ Equity

|

166,869

|

176,172

|

184,874

|

192,963

|

200,425

|

207,246

|

213,412

|

218,911

|

222,045

|

|

Note 2: The Poncini family takes dividends equal to 60 percent of net profits whenever net profits are positive.

“Perhaps we can be a bit more optimistic. Scenario 2 shows that if the Pinot Grigio harvest declined at only 2.5 percent a year instead of 5 percent, our net profits would not decline as quickly. So, we would be able to pay ourselves more dividends by 2023 (a total of EUR 97,598) but the dividends would still be declining and would stop in a few more years.”

He paused again. Everyone nodded thoughtfully.

“Now let’s consider what we might do about this,” Lorenzo said. We will always want to plant a grape which is right for our soil and climate, but why not go with something which is clearly ‘on trend’? Glera looks like the grape of the future. We could also be more efficient with our operations. If we replanted with Glera, we could take the opportunity to use the Guyot planting method which would allow us to harvest mechanically. This would mean we would hire only a few farmers instead of the 30 we hire now to help us with hand-picking.” Despite his efforts to maintain a calm, objective demeanor, enthusiasm was making Lorenzo speak more quickly. Even so, he felt a growing skepticism in the room. “I know what you want to ask me,” he said. “How can we afford to replant, and where does the money come from for a harvester? Well, let me show you.” Lorenzo showed his audience the figures indicating the relative popularity of Glera and Pinot Grigio (see Exhibit 10). He then turned to Scenario 3 (See Exhibit 16).

Exhibit 16. Scenario 3: Grub up old vineyards, plant Glera, sell at average price for Pinot Grigio 2010-2014 Projected income statements 2015-2023 (in €) (condensed)

|

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

2019

|

2020

|

2021

|

2022

|

2023

|

|

Revenues

|

|||||||||

|

Glera sales

(4.84 hectares @ €14,024/ha)

|

67,860

|

0

|

17,308

|

34,956

|

52,943

|

71,270

|

71,949

|

72,627

|

73,306

|

|

Corn sales

|

|

3,330

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EU subsidy

(2014 Italian average plus 5% in each successive year)

|

|

62,504

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TOTAL revenues

|

67,860

|

65,834

|

17,308

|

34,956

|

52,943

|

71,270

|

71,949

|

72,627

|

73,306

|

|

Expenditures

|

|||||||||

|

Lease of harvester (€60,000 at 6% interest per annum)

|

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

|

Grubbing up and sowing corn: 4.84 hectares @ €6,500/ha

|

31,460

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Establishing Glera, including trellising, fertilizing, planting 4.84 ha @ €5,000/ha

|

|

26,620

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Labor (1)

|

|||||||||

|

. Pruning

|

10,715

|

3,647

|

6,099

|

7,378

|

9,297

|

11,251

|

11,358

|

11,465

|

11,573

|

|

. Cutting back buds

|

23,461

|

7,985

|

12,031

|

16,154

|

20,355

|

24,634

|

24,869

|

25,103

|

24,634

|

|

. Thinning out

|

1,459

|

497

|

748

|

990

|

1,266

|

1,532

|

1,546

|

1,561

|

1,576

|

|

. Harvest

|

7,687

|

2,616

|

3,292

|

2,931

|

3,091

|

3,255

|

3,286

|

3,317

|

3,348

|

|

TOTAL expenditures

|

74,782

|

41,365

|

25,769

|

31,052

|

37,609

|

44,272

|

44,660

|

45,047

|

44,730

|

|

Net profit/loss

Exhibit 16 (continued

|

-6,922

|

24,469

|

-8,461

|

3,904

|

15,334

|

26,988

|

27,289

|

27,581

|

28,576

|

(1) Costs for pruning, cutting back, thinning out, and harvesting are based on the average cost for each item in the past 5 years plus an annual increase of 1%. Harvesting mechanically reduces worker time, reducing expenditure for this item.

Related changes to balance sheet (in €) (condensed)

|

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

2019

|

2020

|

2021

|

2022

|

2023

|

|

|

Total Assets (1)

|

271,609

|

279,272

|

286,916

|

294,569

|

302,222

|

309,875

|

317,528

|

325,181

|

332,835

|

|

|

Total Liabilities

|

109,427

|

108,163

|

138,959

|

142,708

|

144,228

|

141,082

|

137,819

|

134,440

|

130,663

|

|

|

S’holders’ Equity

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Net profit

(from income statement)

|

-6,922

|

24,469

|

-8,461

|

3,094

|

15,334

|

26,998

|

27,289

|

27,581

|

28,576

|

|

|

Shareholders’ dividends (2)

|

0

|

-14,681

|

0

|

-2,342

|

-9,200

|

-16,199

|

-16,373

|

-16,549

|

-17,146

|

Total 92,491

|

|

Total S’holders’ Equity

|

146,630

|

171,099

|

147,957

|

151,861

|

157,994

|

168,793

|

179,709

|

190,741

|

202,172

|

|

(2) The Poncini family takes dividends equal to 60 percent of net profits whenever net profits are positive.

“We can minimize expenditure by leasing, rather than buying, a harvester,” Lorenzo said. “A 60,000 euro harvester leased at 6 percent per annum would cost 3,600 per annum.”

He then explained that he had carefully researched the costs of grubbing up 4.84 hectares of Pinot Grigio and establishing Glera and arrived at generous estimates: EUR 6,000 per hectare and EUR 4,430 per hectare respectively. The projected revenues were, he said, just as conservative. After grubbing up, the family would plant a corn crop to refresh the soil. The sale of the corn crop would bring in EUR 3,300 in 2016. Then Lorenzo discussed revenues.

“I know it takes time for a newly planted vineyard to reach peak yield. So, I have projected only a gradual increase in revenues for the new grape variety: 25 percent each year until it reaches peak yield in 2020. I am also assuming that GIC would pay only a modest annual price per hectare increase for Glera: 1 percent a year. Under the Scenario 3 strategy, dividends would be EUR 92,491 by 2023 and could be expected to continue.”

“But what is your assumed price for Glera?” came a quiet voice from the back of the room. It was Angelo, who until now had been bent over the papers. “And what’s this item here – something about an EU subsidy?” Lorenzo smiled as he looked back at Angelo. “I was coming to those,” he said. “First, the subsidy….” Lorenzo went on to explain what he knew about the criteria for the EU subsidies to restructure vineyards and the subsidy his neighbor had received. Given that EU subsidies had been increasing consistently, Lorenzo estimated that he could reasonably expect an EU subsidy of EUR 62,504 in 2016, that is, the average for Italy in 2014 plus 5 percent in each subsequent year.

“As for the Glera price,” he continued, “we saw earlier that our average annual revenue for Pinot Grigio for the last five years is EUR 14,024, so I assume GIC would pay the same price for our first Glera harvest. I also assume that the price would increase only a little every year, say 1 percent. So, you see, all my estimates in Scenario 3 are quite conservative.”

Lorenzo waited, then went on to show his last slide. There was silence as everyone turned to Scenario 4 (See Exhibit 17).

Exhibit 17. Scenario 4: Grub up old vineyards, replant with Glera, sell at €24,500/ha Projected profit and loss statements 2015-2023 (in €) (condensed)

|

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

2019

|

2020

|

2021

|

2022

|

2023

|

|

Revenues

|

|||||||||

|

Glera sales (4.84 hectares @ €14,500/ha)

|

67,860

|

0

|

17,896

|

36,143

|

54,740

|

73,689

|

74,391

|

75,093

|

75,794

|

|

Corn sales

|

|

3,330

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EU subsidy (2014 Italian average plus 5% in each successive year)

|

|

62,504

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TOTAL revenues

|

67,860

|

65,834

|

17,896

|

36,143

|

54,740

|

73,689

|

74,391

|

75,093

|

75,794

|

|

Expenditures

|

|||||||||

|

Lease of harvester (€60,000 at 6% interest per annum)

|

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

3,600

|

|

Grubbing up and sowing corn: 4.84 hectares @ €6,500/ha

|

31,460

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Establishing Glera, (trellising, fertilizing, planting 4.84 ha @ €5,000/ha)

|

|

26,620

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Labor (1)

|

|||||||||

|

. Pruning

|

10,715

|

3,647

|

6,099

|

7,378

|

9,297

|

11,251

|

11,358

|

11,465

|

11,573

|

|

. Cutting back buds

|

23,461

|

7,985

|

12,031

|

16,154

|

20,355

|

24,634

|

24,869

|

25,103

|

24,634

|

|

. Thinning out

|

1,459

|

497

|

748

|

990

|

1,266

|

1,532

|

1,546

|

1,561

|

1,576

|

|

. Harvest

|

7,687

|

2,616

|

3,292

|

2,931

|

3,091

|

3,255

|

3,286

|

3,317

|

3,348

|

|

TOTAL expenditures

|

74,782

|

41,365

|

25,769

|

31,052

|

37,609

|

44,272

|

44,660

|

45,047

|

44,730

|

|

NET profit/loss

|

-6,922

|

24,469

|

-7,874

|

5,090

|

17,131

|

29,417

|

29,731

|

30,046

|

31,064

|

(1) Costs for pruning, cutting back, thinning out, and harvesting are based on the average cost for each item in the past 5 years plus an annual increase of 1%. Harvesting mechanically reduces worker time, reducing expenditure on labor.

Related changes to balance sheet (in €)

|

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

2019

|

2020

|

2021

|

2022

|

2023

|

|

|

Total Assets (1)

|

271,609

|

279,262

|

286,916

|

294,569

|

302,222

|

309,875

|

317,528

|

325,181

|

332,835

|

|

|

Total Liabilities

|

121,551

|

104,735

|

134,944

|

137,507

|

138,308,

|

134,194

|

129,955

|

125,590

|

120,817

|

|

|

S’holders’ Equity

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Net profit (from income statement)

|

-6,922

|

24,469

|

-7,874

|

5,050

|

17,131

|

29,417

|

29,731

|

30,046

|

31,064

|

|

|

S’holders’ dividends (2)

|

0

|

-14,681

|

0

|

-3,054

|

-10,279

|

-17,650

|

-17,839

|

-18,028

|

-18,638

|

Total dividends

100,169

|

|

Total S’holders’ Equity

|

150,058

|

174,527

|

151,972

|

157,062

|

163,914

|

175,681

|

187,573

|

199,592

|

212,017

|

|

(2) The Poncini family takes dividends equal to 60% of net profits whenever net profits are positive.

“But GIC might be willing to pay more for Glera, as it is becoming so popular. Perhaps they would be willing to pay EUR 24,500 per hectare. Scenario 4 shows that situation. It is otherwise the same as Scenario 3. If GIC were to pay EUR 24,500 per hectare, we could distribute dividends of EUR 100,169 to the family and we could expect these healthy returns to continue into the foreseeable future.”

Relieved that the presentation was over, Lorenzo picked up his glass of wine. Moving towards his seat, he said,

“So those are my ideas. Thank you all for hearing me out,” he said. “It has been good to think this through systematically. I am keen to know what you all think.”

There was a silence while people absorbed what Lorenzo had said. No-one seemed to want to speak. So, Carlo turned to Luigi.

“You know our family well, Luigi, and now you know a lot about our grape growing. We know you are a fine grower and an equally fine business person. What are your thoughts? Would you like to tell us how you see the situation, and what we should do?”

NOTE ON HOW RESEARCH DATA WERE GATHERED

The case originated in discussions undertaken with the protagonist, Lorenzo Poncini, when he visited Australia in 2015. Lorenzo was interviewed extensively in person by the first author [name omitted], about the Poncini family business and its issues. After Lorenzo’s return to Italy the discussions continued by email. Other family members were interviewed in 2015 and 2016.

Other sources of information included financial documents from the Poncini firm, information supplied by GIC cooperative, and the Italian wine media.

The names of the business, the cooperative, and people in the case have been disguised.

[1] Trento is the capital of Trentino-South Tyrol Region (Regione Trentino Alto Adige). This region has two autonomous provinces: the Province of Trento and the Province of Bolzano/Bozen.