Adeline Alonso Ugaglia | Stéphane Ouvrard

Date Accepted: June 14, 2020 PDT

Keywords: Tradition, Place de Bordeaux, terroir, en primeur, quality wines, innovation, differentiation strategy, branding, sustainable business model, direct sales - fixed vs. variable costs.

Balancing Tradition and Innovation in Bordeaux: A Differentiation Strategy for Château Luchey-Halde

Download PDF of Full Research Article

In the spring of 2019, Pierre Darriet, the director of operations of Château Luchey-Halde, was making his rounds through the vineyards. Château Luchey-Halde was a wine producer in Bordeaux, France. As Pierre admired the delicate leaves of the fine Cabernet Sauvignon just coming into bud, he reflected on the attributes that had made Château Luchey-Halde unique. Pierre regarded innovation as the key to improving the quality of a wine. However, a question kept nagging at him: how can a producer garner attention for being innovative and sustainable in the French wine sector when a wine’s tradition was considered by that country’s distributors and consumers to be its most respected attribute? Pierre reflected:

The two are not incompatible...We can be innovative while communicating on tradition...It is important to innovate in the wine sector, as in any sector of activity. This makes it possible to differentiate oneself from one’s competitors. Today, to be successful, you have to have something distinctive that competitors do not have.

Château Luchey-Halde was owned and managed by Bordeaux Sciences Agro, the National School of Agronomic Sciences of Bordeaux-Aquitaine. The winery was not only a tool for teaching viticulture and oenology to engineering and master’s students, but also a successful wine brand, producing 115,000 bottles a year (100,000 bottles of red and 15,000 of white). It sold an estimated 78,000 bottles of wine a year. Château Luchey-Halde relied on cutting-edge technology in viticultural practices, while pursuing sustainability to preserve long-standing regional traditions in terroir and winemaking. In France, a wine’s reputation was a function of its tradition—know-how, terroir, and the appellation d’origine contrôlée (AOC), also known as the protected designation of origin.[i] The French wine consumer believed that a wine’s reputation was of considerable importance, which led to strict regulations on viticulture and winemaking in that country since the 1930s.

Faced with declining wine consumption in France and an increasingly competitive international marketplace for wine sales, Pierre questioned whether notions such as tradition, know-how, and terroir could still be viewed as key factors of success. As Pierre looked out over the vineyards, he wondered how to best tell the Château Luchey-Halde story so that the estate would become a recognized brand in the world of great wines of Bordeaux. Could a new positioning strategy that blended tradition, innovation, and environmental stewardship help to improve sales? Could Château Luchey-Halde’s business model accommodate both tradition and innovation in order to differentiate its brands and create lifetime customer value in a crowded marketplace for wine?

BORDEAUX WINE AND THE WINE FUTURES SYSTEM

Organization of the wine sector in Bordeaux

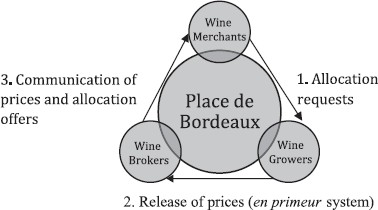

Historically, the wine sector in Bordeaux was predicated upon close relationships between wine growers (estates), brokers (courtiers), and wine merchants (négociants). Wine growers either sold their wines directly or sold them through the wine merchants. The Bordeaux market for wine comprised a network of estate owners, wine brokers, and wine merchants involved in the Bordeaux wine trade (see Exhibit 1). From its creation in the 19th century, the Bordeaux market, although sometimes criticized, remained a unique wine trade model, viewed as a benchmark by some industry observers at the international level. The Bordeaux market encompassed an estimated 7,000 wine growers, 80 wine brokers, and 300 wine merchants. Wine merchants worked closely with wine brokers, real wine experts who played an intermediary role between wine growers and the wine merchants. A wine broker took part in the château’s pricing policy and was paid a percentage on transactions (two percent in Bordeaux). This profession was governed and ruled by the Regional Chamber of Commerce and Industry. For additional information on what was termed the en primeur wine futures system and a comparison with the three-tier distribution system used in the United States, see Appendix 1.

Exhibit 1

Bordeaux Market (“La Place de Bordeaux”)

According to French wine industry researchers Hadj Ali and Nauges, wine futures sales referred to a wine sold several months after the harvest, while it was still in barrels. At the time of wine futures sales, the price of the wine (produced by the château for a particular vintage) was chosen by each individual producer. The wine futures market took place every year in the spring and represented one of the most important events for the Bordeaux market. This type of sale allowed producers to gain “cash-in-hand” before their wine was bottled. At the same time, it enabled buyers to acquire potentially rare wines at possible bargain prices, hence attracting more and more financial speculation.[ii]

Three ranking systems were used for red wines produced in Bordeaux:

- The first ranking for wines from the Médoc dated back to 1855 and had remained largely unchanged. Wines were classified following a five-tier classification system ranging from top-quality Premiers Cru or First Growth (denoted here as ME-1) to Cinquièmes Cru or Fifth Growth (ME-5). Later on, in 1920, some of the non-ranked châteaux were classified in a sixth group called Cru Bourgeois (ME-6).

- Saint-Émilion wines were formally classified in 1955 (and subsequently revised every ten years) and followed a three-tier ranking system: Premiers Grands Cru Classés A (SE-1), Premiers Grands Cru Classés B (SE-2), and Grands Cru Classés (SE-3).

- Wines from the Graves (GR) were officially classified from the beginning of 1953.

CHÂTEAU LUCHEY-HALDE

Located at Mérignac in the prestigious Pessac-Léognan AOC, in the heart of the Graves vineyards, Château Luchey-Halde covered 23 hectares (see Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2

Appellations of the Bordeaux Region

The estate was initially divided into two châteaux: Château Luchey and Château Halde. Both estates were located on a terroir which was first planted with vines during the Roman era. These two estates were purchased in 1919 by the French Army which wanted land dedicated to sports activities and military training programs. Transformed in the 1920s into a military training camp by the Ministry of Defense, Château Luchey-Halde was eventually put up for sale in 1999 and purchased by Bordeaux Sciences Agro. The University decided to invest in an estate as a veritable showcase for its know-how in agronomy, viticulture, and oenology. The vineyard in 2019 comprised 19 hectares that produced red grape varieties: Cabernet Sauvignon (55 percent), Merlot (35 percent), Cabernet Franc (five percent), and Petit Verdot (five percent). Château Luchey-Halde also owned four hectares producing white grape varieties: Sauvignon Blanc (37 percent), Sauvignon Gris (18 percent), and Semillon (45 percent).

An advanced pedological study was carried out at the initiative of the professors at Bordeaux Sciences Agro in 2000 to ensure optimal planting in the vineyard. It matched grape varieties with their ideal soil types, which revealed the excellent potential of the terroir and the possibility of producing high-quality wines. From this moment, Bordeaux Sciences Agro decided to initiate an ambitious program based on high-density planting, tillage, and respect for the environment. Tillage helped to control soil flora, favoring the deep rooting necessary for the proper nutrition of the vine stock. The average yield was approximately 40hl/ha (while the appellation maximum authorized yield was 50hl/ha) and the estate produced between 100,000 and 120,000 bottles of red and white wines each year (although less than 70,000 at first). See Exhibit 3 for a summary of the key facts and figures for Château Luchey-Halde.

| Area (ha) | 23 hectares |

|---|---|

| Annual Production | Average target of 120,000 bottles No bulk wine |

| AOC | Pessac-Léognan |

| Legal Form | Public establishment for higher agricultural education (Bordeaux Sciences Agro) |

| Head | Prof. Olivier Lavialle |

| Manager | Pierre Darriet (agricultural engineer) |

| Board | Prof. Olivier Lavialle and Pierre Darriet (under the supervision of the governing board of Bordeaux Sciences Agro) |

| Labor Force | Permanent employees: 7 full-time employees (private contracts) 1 full-time employee (public contract) 1 apprentice (student at BSA) + seasonal employees, pickers, service providers |

| From | 1999 |

| Turnover 2016 | 820K€ (78,000 bottles sold, 115,000 produced) |

Source: Pierre Darriet, Château Luchey-Halde

Château Luchey-Halde’s wines and brands

Château Luchey-Halde offered a first and second wine, respectively Château Luchey-Halde and Les Haldes de Luchey in both red and white. See Exhibit 4 for a list of the producer’s per bottle prices. The average selling prices to the public were approximately 25 and 35 Euros per bottle for Château Luchey-Halde, depending on the vintages, and 15 Euros per bottle for Les Haldes de Luchey. For example, the 2017 vintages were partly sold as futures at approximately 15 Euros per bottle for the first wine and 10 Euros per bottle for the second.

|

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

|

Château Luchey-Halde

|

12.42

|

13.59

|

13.29

|

13.02

|

|

Les Haldes de Luchey

|

7.73

|

8.30

|

8.34

|

8.36

|

|

Weighted Average

|

9.29

|

9.78

|

10.31

|

10.38

|

|

Average Price Variation

|

|

5.27%

|

5.42%

|

0.68%

|

In addition to these wines, a cuvée branded U (named after the University) was launched to promote the University of Bordeaux. Based on a blend almost identical to that of the estate’s first wine, U had been sold in the estate’s shop, restaurants in Bordeaux, and nearby universities since 2017. It was especially useful advertising when hosting international professors and researchers during academic events. Ten thousand bottles of U were sold in its first year. Château Luchey-Halde also developed other brands, which were named after the estate. LH², for example, was easily recognizable thanks to its black label and was intended for mass retailing. L by Luchey-Halde was a brand designed for the Swedish market. See Exhibit 5 for the distribution of Château Luchey-Halde’s production by type of wine in 2016.

|

|

Bottles

|

Income €

|

Average Price (€/bottle)

|

|

Château Luchey-Halde (red)

|

30,358

|

394,350.42

|

12.99

|

|

U (red)

|

1,145

|

17,278.05

|

15.09

|

|

Wit4 Luchey (red)

|

59

|

2,610.75

|

44.25

|

|

|

31,562

|

414,239.22

|

13.12

|

|

Château Luchey-Halde (white)

|

2,523

|

29,626.40

|

11.74

|

|

U (white)

|

141

|

1,907.50

|

13.53

|

|

|

2,664

|

31,533.90

|

11.84

|

|

Les Haldes de Luchey (red)

|

39,982

|

334,852.28

|

8.38

|

|

Les Haldes de Luchey (white)

|

4,721

|

38,650.25

|

8.19

|

|

|

44,703

|

373,502.53

|

8.35

|

|

Total

|

78,930

|

819,275.65

|

10.38

|

OPERATIONS

Château Luchey-Halde was managed in close collaboration between Olivier Lavialle, the director of Bordeaux Sciences Agro, and Pierre Darriet, the estate’s manager. Olivier focused on the global strategy of the estate and administrative issues while Pierre, whom Olivier considered to be a “man of the soil” with a passion for vines and wine, managed the vineyard and the wine processing. Both desired to make the Luchey-Halde estate a recognized brand in the world of great wines of Bordeaux and discussed the proposed positioning strategy to make this goal a reality. The partners, together with the management team, had set a sales target of 120,000 bottles per year for the 2013–2016 period, a target that they were not able to reach. Pierre reflected:

For the future, we want to position ourselves toward the top-end of the market. Of course, this requires irreproachable and consistent product quality, but this is not enough. We also need to have a real “proposition of value” to offer our customers. After tasting a wine from our estate, they must remember us!

In 2017, a five-year strategic plan was presented to the board of directors. This plan included an increase in the number of bottles sold annually from 78,000 to 150,000, a reduction of inventories through a destocking operation, a balance of sales with 50 percent in France and 50 percent to export markets, an introduction of a marketing promotion about the estate’s sustainable development, and an implementation of a transfer of knowledge with engineering students.

Château Luchey-Halde’s primary emphasis was on environmental issues, yet its core activity remained the production and marketing of wine. To somewhat diversify its business, Château Luchey-Halde provided a room rental service, managed by an outside servicing company. This helped support the visibility of the estate. Most of the time, the room was hired out for weddings. It was also available for Bordeaux Sciences Agro events, such as graduation ceremonies, seminars, and meetings. Additionally, from April through September 2017, the château welcomed an oenotourism intern to manage customer demand.

SALES STRATEGY

Sales in France and Abroad

Château Luchey-Halde practiced short sales, which referred to direct sales and sales with no more than one intermediary body between the producer and the consumer. Château Luchey-Halde did not use traders and wine merchants because the volumes it produced were too low. Additionally, the purchase of wine by traders was no longer automatic in Bordeaux. There was no guarantee, either in volume or in price, and the production costs were high due to the quality of the wine produced. This distribution channel was also less profitable than direct sales.

The choice to practice short sales did not help sales to take off at first, especially in the absence of a positioning strategy and a staff person to oversee promotion (one equivalent full-time employee dedicated to commercial activities). Indeed, although dealing with wine merchants would have enabled Château Luchey-Halde to sell potentially large volumes, the direct-sales system required them to build a real and efficient positioning strategy step-by-step starting in 2015. This resulted in the recent creation of a portfolio of major customers in France and abroad, whereas customers were previously only local (cafés, hotels, and restaurants in Gironde). An analysis of the cost/benefit ratio led them to focus the positioning strategy of the estate upon the most important and least time-consuming customers.

Today, Château Luchey-Halde sells most of its wines in France (70 percent of total turnover). In this market, its main distributor was the French company Cash Vin. Because of its many geographical locations in Bordeaux and its region, Cash Vin guaranteed effective representation of the estate throughout Gironde. In addition, the estate marketed its wines through a network of wine stores.

The main export markets were Switzerland (20 percent of total turnover), Belgium (two percent), and more recently Sweden (eight percent). The wines sold in Switzerland were essentially first wines that were better appreciated there than domestically. Since 2017, Sweden had represented a new market (7,000 bottles had been sold there, a turnover rate of 65,500 Euros). In this country, wines were sold through a state monopoly. In the future, the Swedish market should constitute a recurrent commercial outlet for the estate (Exhibit 6).

|

|

Income 2016 (k€)

|

%

|

|

Bottles sold (2016)

|

%

|

|

France

|

573.5

|

70%

|

France

|

53,251

|

67%

|

|

Switzerland

|

163.8

|

20%

|

Switzerland

|

17,786

|

23%

|

|

Sweden

|

65.5

|

8%

|

Sweden

|

7,104

|

9%

|

|

Belgium

|

16.4

|

2%

|

Belgium

|

789

|

1%

|

|

Total

|

819.2

|

100%

|

Total

|

78,930

|

100%

|

Source: Luchey-Halde Estate

Olivier and Pierre considered other markets for wine sales, namely the United States and Canada. Château Luchey-Halde was a member of the Bordeaux vignerons, a group of 13 independent winemakers sharing the same marketing methods (direct sales or controlled sales through brokers and wine merchants). Members of this group pooled their prospecting costs and accessed distant foreign markets through joint commercial proposals. In this way, customers benefited from a single contact for a wide range of wines. Bordeaux vignerons offered a diversified range of wines in which Château Luchey-Halde occupied a dominant position as the only estate representing the Pessac-Léognan appellation. In general, the management of the estate had great expectations for export markets, in terms of number of bottles sold, especially for the first wine. The U.S. market was expected to expand in 2018 as a result of strong prospecting efforts. By the end of 2017, another business opportunity had opened up in the U.K. following the signing of an exclusive contract with a single distributor.

BRANDING OPTIONS

In order to meet the strategic objectives set out by the board of directors, Pierre felt that he needed to hone his brand’s messaging. He would need to integrate into his brand image both Château Luchey-Halde’s tradition and innovation as a way to differentiate and create value. Additionally, he would have to communicate on the estate’s up-to-date viticultural practices, such as agro-ecology, as this approach provided credibility, especially with export markets. He commented:

Our communication with the market was centered on the storytelling of the estate, as a young and dynamic vineyard owned by the National School of Agronomy. The estate represented a beautiful blend of tradition and modernity that is partly explained by its history.

Tradition

Château Luchey-Halde was actually a very young estate, replanted in the 2000s on a very old terroir. Although terroir was a traditional and not particularly distinctive factor in an appellation like Pessac-Leognan, promoting the estate’s history added value to the tremendous amount of work that had been put into this estate. This temporal duality was reflected in the estate’s architectural styles: An old Chartreuse building and vaulted cellars dating back to the 18th century offset the modern and high-performance installations built in 2002.

For many châteaux and estates located in prestigious appellations of the Bordeaux wine region, terroir remained an essential focus of marketing communications. Terroir was a concept that encompassed many dimensions such as climate, soil, and cultural practices. It also referred to practices that guaranteed typicity and quality. The Graves terroir (Exhibit 2), including the one founded in 1987 in the Pessac-Léognan appellation, stemmed from a long and complex history closely linked to the birth of the Garonne river, the changes in its route, and successive glacial periods during the Quaternary era. It was viewed as a real geological patchwork, as its name suggests. It was composed of pebbles, stones, gravels of varying size, sands mixed with limes and clays, pure sand, or clay soils. Those areas of great permeability with poor soils and slopes, which favor water flow, guaranteed optimal control of the water input for the vines. The Graves soil reflected the sun’s rays, gradually redirecting the heat onto the grapes and, thus, contributing to the ripening process. The varying thickness of the soil (from 20 cm to three meters or more), with no real homogeneity below ground level, provided the basis for diversity and the different expressions, characteristics, and nuances of top-quality Pessac-Léognan wines. The climate, under the influence of the Atlantic Ocean, was typical of the Gironde—mild and favorable for wine because of its gentleness.

With a surface area of 1600 ha, the Pessac-Léognan appellation was regulated by rules and specifications like all other AOCs.[iii] For red wines, the main varietals were Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, Malbec, and Carmenere, whereas Sauvignon Blanc, Semillon, and Muscadelle were the primary white wine varietals. The minimum density for planting was 6,500 plants/ha, but generally, the average was around 9,000 plants/ha. Authorized yields were 45 hl/ha for red wines (80 percent of total production) and 48 hl/ha for white. The appellation communicated on its history and advocated for a vineyard midway between youth and maturity.

Innovation

Pierre believed that, “innovation was not only about the product. It could take on various forms: wine-growing methods, respect for the environment, optimization of an internal organization, management of teams, etc.” He further explained:

We are aware that the competition was intense with famous châteaux in the Pessac-Léognan appellation...Some of them already had well-established brands. However, we had a lot of assets to put forward. First, an identity of our own: managed by a National Engineering School, the Luchey-Halde estate enjoyed an innovative image on the technical level.

Sustainability

With a strong commitment to sustainable development and environmental innovation, Bordeaux Sciences Agro thrived on being exemplary in the sustainable way it ran its urban vineyard. Eager to continuously improve its environmental performances, the estate had been a member of the first association for Environmental Management Systems (EMS) of Bordeaux wines since 2012. The association experienced considerable difficulty at first with only 27 estates as members. Nevertheless, it helped improve the management of the estate through input reduction, waste reduction, and sorting. The estate was also a member of a European![]() Economic Interest Grouping (EEIG)[iv], which was committed to reducing agrochemical products. In addition, because of its urban location, Bordeaux Sciences Agro had decided to include the human environment in its approach by developing prevention and awareness-raising initiatives aimed at its own neighborhood (informing people about the spraying calendar).

Economic Interest Grouping (EEIG)[iv], which was committed to reducing agrochemical products. In addition, because of its urban location, Bordeaux Sciences Agro had decided to include the human environment in its approach by developing prevention and awareness-raising initiatives aimed at its own neighborhood (informing people about the spraying calendar).

Because the estate belonged to an agronomy school, it developed an environmental approach based upon agroecological principles. It applied these practices to the vineyards and surrounding land. One objective was to manage areas not cultivated under wine grapevines in order to enrich the biodiversity that already existed on site. For example, an old shooting range, located in the heart of a small wood, was destroyed and replaced by a project that was respectful of both biodiversity and the environment. Many tree species were planted to favor fauna and flora. In spring 2017, two apiaries were set up with the help of a beekeeper to demonstrate that the estate’s viticultural practices were not harmful for bees.

Social Innovation

From 2015, Bordeaux Sciences Agro had been financing an agroecological program based upon innovation and research. This program aimed to develop both environmentally-friendly and economically-viable practices. Since 2015, the estate had benefited from an annual call for projects from Bordeaux Sciences Agro (for both research and know-how transfer actions). It was also part of an ‘Agroecological Transition’ project for the period 2016–2018, which was financed by a national program for agriculture and rurality development initiated by the Ministry of Agriculture. The estate also participated in a Digilab project dedicated to the development and diffusion of connected devices in order to reduce inputs, although this teaching activity would sometimes infringe upon its business imperatives. For example, experiments were made in the vineyard to test decision rules in order to spray less pesticides in the vineyard (teledetection of the diseases). If the experiments failed, the château would lose a part of the harvest. This project was initiated within the framework of an innovation laboratory in the New Aquitaine region. The estate positioned itself upstream in order to benefit from a ‘first-mover advantage’ as alleged by Lieberman and Montgomery (1988).

Château Luchey-Halde was also at the center of knowledge transmission. This estate was an educational tool, easily accessible to engineering students who wanted to deepen their knowledge of production, financial management, or marketing topics. It had welcomed many interns and apprentices who spent their training period at the winery. This privileged link between teaching and research was considered by University administrators and faculty to be a key driver in Château Luchey-Halde’s quest to achieve excellence in innovation.

LOOKING FORWARD

In late 2019, Olivier and Pierre hoped to decide upon a strategy to reach their commercial goals, mindful of the inventory already available for sale out to 2022. They wondered if their product lines needed to be repositioned to reach a top-end market, how to optimize a mix of distribution channels for Bordeaux and other markets, and how to promote the winery’s sustainability initiatives while remaining mindful that tradition and terroir were more highly valued in the Bordeaux region and France. Olivier and Pierre agreed upon an ongoing innovation process to improve the quality of the wine. Finding a balance between innovation and tradition would be crucial for Château Luchey-Halde to remain competitive when facing an uncertain future marketplace.

Appendix 1. The Bordeaux Wine Futures System vs. United States’ Three-Tier System

In Bordeaux, wine futures or en primeur had remained more or less a tradition since the 18th century, when a group of merchants devised a system for visiting the châteaux a few months before the harvest and for valuing and buying the grapes off the vine. This ancestral practice has led to the modern-day wine futures system which was introduced in the 1980s. In the United States, the three-tier system, comprised of importers or producers, distributors, and retailers, was inaugurated to tightly control alcoholic beverage sales upon the repeal of Prohibition in 1933. Below are explanations of these two different systems in greater detail.

The Bordeaux wine futures system

According to Bordeaux wine industry observers,

The en primeur system is a futures system whereby customers (wine merchants of Bordeaux, distributors, final buyers) buy (and pay for) wine today, to be delivered about 18 months later. When buying en primeur, final buyers are paying in full at that specific date for the wine. For the wine merchants of the Bordeaux Place, the payment process is negotiated with the estate—one third can be paid when the wine is proposed on allocation, one third after six months, and one third on delivery time…The en primeur campaign starts early in the estate year. As weather contributes to the quality of the wine, the final four weeks before harvest time determine the overall quality of the wine, and its price. During the following weeks, producers send ‘signals’ through various channels about the quality of the vintage. Producers are in fact preparing the market that the price of the vintage may be high this current year due to good quality. At the same time, distributors around the world would counteract, suggesting the market is not willing to pay that much for the vintage. By the end of March, wine producers will officially present their wine to the brokers and merchants of the Bordeaux Place. Following this presentation, the wine is officially unveiled to journalists, wine critics, distributors and all other wine professionals during the en primeur week, usually the first week of April.[v]

The United States’ Three-Tier System

In addition to federal regulators, the 50 individual U.S. states and District of Columbia administered and levied their own excise, sales, and other taxes, and regulated the distribution and sale of alcohol through a ‘three-tier system,’ i.e. from producer to distributor to retailer. A widening chasm was appearing between large mass merchandisers that pursued broad or mass markets and small-mid size producers that pursued focused target markets via differentiated products, i.e., a niche strategy. Successful small-mid size wineries—i.e., under $60 million in revenue—were said by industry analysts to be learning and applying industry best practices, such as improving management team knowledge of consumer branding in regional, national, and export markets. Nevertheless, large distributors, which typically purchased branded wines from wineries at 50 percent of retail prices, increasingly managed all wine at retail and restaurants.

In 2019, two U.S. distributors, Southern Wine & Spirits/ Glazer’s and Republic National Distributing Co./Young’s Market, “accounted for $27 billion in wine sales or more than half of the nearly $50 billion U.S. consumers spent on domestic wines per year,” according to Wines & Vines Analytics.[vi] Concentration in the three-tier distribution channel severely limited the opportunity for a small, 1,000–20,000 case (12,000–240,000 bottles) producer, because a couple of good placements at restaurants would exhaust that inventory before the restaurant even had time to reprint the wine list to feature the wines. The days when business models were conducted on the premise that 80 percent of sales came from 20 percent of the products available were rapidly becoming numbered.

References

Managerial Summary

The case of Château Luchey-Halde provides adopters and students with an opportunity to discuss the pros and cons of a strategy balanced between tradition (terroir, heritage, family values, etc.) and innovation (technological edge, new viticultural practices, sustainable development, etc.) in order to achieve differentiation. Located on the left bank of the Garonne river, in the famous “Graves” terroir, Château Luchey-Halde is owned and managed by a famous Agricultural Engineering School, Bordeaux Sciences Agro. Château Luchey-Halde’s business model is based upon a direct-sales strategy, which is relatively uncommon in Bordeaux. Company manager Pierre Darriet is pondering whether or not to pursue commercial distribution which would involve going through the Bordeaux Market Place (‘la Place de Bordeaux’), and therefore depending on wine merchants’ demand and prices every year – and weighing its potential impact on the current direct-sales system.[i]

A Château that decides to go through the Bordeaux Market Place avoids bearing all the marketing costs, since those are outsourced to the wine merchants. Thanks to their historical experience in the wine trade and their strong knowledge of international markets, wine merchants have strong commercial departments, enabling them to manage selling and marketing costs. On the other hand, when bypassing the wine merchants, e.g. when opting for a direct-sales system, the Châteaux owners benefit from higher gross profit margins - although this choice implies additional operating costs.

Bordeaux’s wine market, traditionally named “Place de Bordeaux”, relies on an original and unique distribution system involving different actors (wine growers, brokers and wine merchants).[i] In this system, which is specific to Bordeaux, Châteaux do not sell directly to final consumers or to distributors but to wine merchants. Having a strong knowledge of international markets, the latter negotiate “allocations” with Châteaux owners with the help of wine experts called courtiers (brokers). Seen as a fundamental part of the region’s institutional culture (Ouvrard and Taplin, 2018), this institutionalized, long-standing distribution system (more than 300 years old) is not adopted by all the wine estates.

Although Château Luchey-Halde is located on a very famous terroir such as Pessac-Léognan (Bordeaux region, France), that alone is not in itself sufficient to make it a successful, sustainable business.

Because of the long-standing distribution model that is largely reliant upon wine merchants in France, direct to consumer sales of wines in France, much less by Bordeaux region producers, has had limited coverage in the wine business research field. Can a Bordeaux winery adopt a direct-to-consumer sales system in order to generate higher margins, even if it also incurs higher operating costs (marketing and distribution expenses)? That is the strategic dilemma that Château Luchey-Halde’s managers are pondering, implying the need to consider a case to be made that would provide a balance between tradition and innovation — and attendant impacts on wine positioning and pricing strategies.

That said, the question remains as to whether or not a small producer like Château Luchey Halde can do both: innovate and capitalize upon what Alonso and Nauges (2007) call the “reputation premium” for wines produced from the Bordeaux region. As Alonso and Nauges write,

…reputation premium - driven by quality-based ranking - is very high in an area such as Bordeaux, which benefits from a long-established reputation in wine making. The “reputation premium” driven by the quality-based classification significantly outweighs any effect driven by objective measures of past quality or the premium associated with short-term changes in current quality. [Alonso and Nauges, 2007 : 101]

Technological innovations comprise new products and processes and significant technological changes of products and processes.

Château Luchey-Halde has several innovative assets: its circular cellar, its story-telling and its links with education and research, but also its environmentally-friendly technical route. Through direct sales, the estate gets an opportunity to create new value around the quality and the story of the wine, and to appropriate it bypassing the traditional intermediaries, finally combining tradition and innovation to set an efficient business model.